Comments: No Comments

How to Effectively Resource Compliance Obligations

Regulatory enforcement, customer and supply chain audits, and internal risk management initiatives are all driving requirements for managing regulatory compliance obligations. Many companies—especially those that are not large enough for a dedicated team of full-time staff—struggle with how to effectively resource their regulatory compliance needs.

Striking a Balance

Using a combination of in-house and outsourced resources can provide the appropriate balance to manage regulatory obligations and maintain compliance.

Outsourcing provides an entire team of resources with a breadth of knowledge/experience and the capacity to complete specific projects, as needed. At the same time, engaging in-house resources allows the organization to optimize staff duties and ensure that critical know-how is being developed internally to sustain compliance into the future.

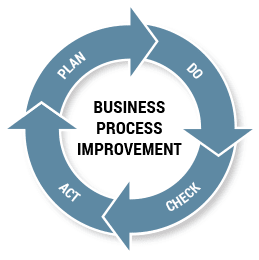

Programmatic Approach to Compliance Management

Taking a balanced and programmatic approach that relies on internal and external resources and follows the three phases outlined below allows small to mid-size companies to create standardized compliance management solutions and more efficiently:

- Identify issues and gaps in regulatory compliance

- Achieve compliance with current obligations

- Realize improvements to compliance management

- Gain the ability to review and continually improve compliance performance

Phase 1: Compliance Assessment

A compliance assessment provides the baseline to improve compliance management and performance in accordance with current business operations and future plans. The assessment should answer the following questions:

- How complete and robust is the existing compliance management program in comparison with standard industry practice?

- Does it have the capability to yield consistent and reliable regulatory compliance assurance?

- What improvements are needed to consistently and reliably achieve compliance and company objectives?

It is important to understand how complete, well-documented, understood, and implemented the current processes and procedures are. Culture, model, processes, and capacity should all be assessed to determine the company’s overall compliance process maturity.

Phase 2: Compliance and Program Improvements

The initial analysis of the assessment forms the basis for developing recommendations and priorities for an action plan to strengthen programs, building on what already exists. The goal of Phase 2 is to begin closing the compliance gaps identified in Phase 1 by implementing corrective actions, including programs, permits, reports, training, etc.

Phase 2 answers the following questions:

- What needs to be done to address gaps and attain compliance?

- What improvements are required to existing programs?

- What resources are required to sustain compliance?

Phase 3: Ongoing Program Management

The goal of Phase 3 is to improve program processes to eliminate compliance gaps and transition the company from outsourced compliance into compliance process improvement/program development and implementation. This is done by managing the eight functions of compliance—identifying what’s needed, who does it, and when it is due. Ongoing maintenance support may include periodic audits, training, management review assistance, Information Systems (IS) support, and other ongoing compliance activities.

Case Study

For one Kestrel client, business growth has increased at a rate prompting proactive management of the company’s regulatory and compliance obligations. Following a Right-Sized Compliance approach, Kestrel assessed the company’s current compliance status and programs/processes/procedures against regulatory requirements. This initial assessment provided the critical information needed for the Kestrel team to help guide the company’s ongoing compliance improvements.

Coming out of the onsite assessment, Kestrel identified opportunities for improvement. Using industry standard program templates, in combination with operation-specific customization, Kestrel created programs to meet the identified improvement from the assessment. Kestrel then provided onsite training sessions and is working with the company to develop a prioritized action plan for ongoing compliance management.

Using the appropriate methods, processes, and technology tools, Kestrel’s programmatic approach is allowing this company to implement EHS programs that are designed to sustain ongoing compliance, achieve continual improvements, and manage compliance with efficiency through this time of accelerated growth.

Making the Connection

Kestrel’s experience suggests that the connection between management and compliance needs to be well synchronized, with reliable and effective regulatory compliance commonly being an outcome of consistent and reliable program implementation. This connection is especially important to avoid recurring compliance issues.

Following a programmatic approach allows companies to realize improvements to their compliance management and:

- Organize requirements into documented programs that outline procedures, roles/responsibilities, training requirements, etc.

- Support management efforts with technology tools that create efficiencies and improved data management

- Conduct the ongoing monitoring and management that are vital to remain in compliance

- Gain the inherent capacity, capability, and maturity to comply, review, and continually improve compliance performance

Comments: No Comments

Compliance Assurance Review

An audit provides a snapshot in time of a company’s compliance status. An essential component of any compliance program—health and safety, environmental, food safety—an audit captures compliance status and provides the opportunity to identify and correct potential business losses. But what about sustaining ongoing compliance beyond that one point in time? How does a company know if it has the processes in place to ensure ongoing compliance?

Creating a Path to Compliance Assurance

A compliance assurance review looks beyond the “point-in-time” compliance to critically evaluate how the company manages compliance programs, processes, and activities, with compliance assurance as the ultimate goal. It can also be used as a process improvement tool, while ensuring compliance with all requirements applicable to the company.

This type of review is ideal for companies that already have a management system in place or strive to approach compliance with health and safety, environmental, or food safety requirements under a management system framework.

Setting the Scope

The scope of the review is tailored to a company’s needs. It can be approached by:

- Compliance program/topic where the company has had routine compliance failures

- Compliance program/topic that presents a high risk to the company

- Compliance program/topic that spans across multiple facilities that report to a central function

- Location/product line/project where the company is looking to streamline a process while still ensuring compliance with multiple legal and other requirements

While each program, project, or location may differ in breadth of regulatory requirements, enforcement priorities, size, complexity, operational control responsibilities, etc., all compliance assurance reviews progress through a standard process that ties back to the management system.

Continual Compliance Improvements

Through a compliance assurance review, the company will define and understand:

- Compliance requirements and where regulated activities occur throughout the organization

- Current company programs and processes used to manage those activities and the associated level of program/process maturity

- Deficiencies in compliance program management and opportunities for improvement

- How to feed review recommendations back into elements of the management system to create a roadmap for sustaining and continually improving compliance

OSHA: Using Drones for Inspections

What was once a very niche market, drones are emerging into an important new phase: everyday use of drone technology in the workplace. It’s no longer just tech-savvy companies that are using drones. Enterprise-level drone operations are becoming a big deal—and not just in industry. During 2018, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) reportedly used drones to conduct at least nine inspections of employer facilities.

OSHA’s drones were most frequently used following accidents at worksites that were considered too dangerous for OSHA inspectors to enter—a common and important benefit of the drone technology. However, is likely that OSHA’s use of drones will quickly expand to include more routine facility reviews, as drones have the ability to provide OSHA inspectors a detailed view of a facility, expanding the areas that can be easily viewed and reducing the time required to conduct an inspection on the ground.

Employers must currently grant OSHA permission to conduct facility inspections with drones, and there are many implications industry must consider in giving this permission. Read the full article in EHS Today to learn more.

Comments: No Comments

5 Questions to Implement Predictive Analytics

How much data does your company generate associated with your business operations? What do you do with that data? Are you using it to inform your business decisions and, potentially, to avoid future risks?

Predictive Analytics and Safety

Predictive analytics is a field that focuses on analyzing large data sets to identify patterns and predict outcomes to help guide decision-making. Many leading companies currently use predictive analytics to identify marketing and sales opportunities. However, the potential benefits of analyzing data in other areas—particularly safety—are considerable.

For example, safety and incident data can be used to predict when and where incidents are likely to occur. Appropriate data analysis strategies can also identify the key factors that contribute to incident risk, thereby allowing companies to proactively address those factors to avoid future incidents.

Key Questions

Many companies already have large amounts of data they are gathering. The key is figuring out how to use that data intelligently to guide future business decision-making. Here are five key questions to guide you in integrating predictive analytics into your operations.

-

What are you interested in predicting? What risks are you trying to mitigate?

Defining your desired result not only helps to focus the project, it narrows brainstorming of risk factors and data sources. This can—and should—be continually referenced throughout the project to ensure your work is designed appropriately to meet the defined objectives.

-

How do you plan to use the predictions to improve operations? What is your goal of implementing a predictive analytics project?

Thinking beyond the project to overall operational improvements provides bigger picture insights into the business outcomes desired. This helps when identifying the format results should be in to maximize their utility in the field and/or for management. In addition, it helps to ensure that the work focuses on those variables that can be controlled to improve operations. Static variables that can’t be changed mean risks cannot be mitigated.

-

Do you currently collect any data related to this?

Understanding your current data will help determine whether additional data collection efforts are needed. You should be able to describe the characteristics of data you have, if any, for the outcome you want to predict (e.g., digital vs. paper/scanned, quantitative vs. qualitative, accuracy, gathered regularly, precision). The benefits and limitations associated with each of these characteristics will be discussed in a future article.

-

What are some risk factors for the desired outcome? What are some things that may increase or decrease the likelihood that your outcome will happen?

These factors are the variables you will use for prediction in the model. It is valuable to brainstorm with all relevant subject matter experts (i.e., management, operations, engineering, third-parties, as appropriate) to get a complete picture. After brainstorming, narrow risk factors based on availability/quality of data, whether the risk factor can be managed/controlled, and a subjective evaluation of risk factor strength. The modeling process will ultimately suggest which of the risk factors significantly contribute to the outcome.

-

What data do you have, if any, for the risk factors you identified?

Again, you need to understand and be able to describe your current data to determine whether it is sufficient to meet your desired outcomes. Using data that have already been gathered can expedite the modeling process, but only if those data are appropriate in format and content to the process you want to predict. If they aren’t appropriate, using these data in modeling can result in time delays or misleading model results.

The versatility of predictive analytics can be applied to help companies analyze a wide variety of problems when the data and desired project outcomes and business/operational improvements are well-defined. With predictive analytics, companies gain the capacity to:

- Explore and investigate past performance

- Gain the insights needed to turn vast amounts of data into relevant and actionable information

- Create statistically valid models to facilitate data-driven decisions

Comments: No Comments

OSHA Clarifies Position on Incentive Programs

OSHA has issued a memorandum to clarify the agency’s position regarding workplace incentive programs and drug testing. OSHA’s rule prohibiting employer retaliation against employees for reporting work-related injuries or illnesses does not prohibit workplace safety incentive programs or post-incident drug testing. The Department believes that these safety incentive programs and/or post-incident drug testing is done to promote workplace safety and health. Action taken under a safety incentive program or post-incident drug testing policy would violate OSHA’s anti-retaliation rule if the employer took the action to penalize an employee for reporting a work-related injury or illness rather than for the legitimate purpose of promoting workplace safety and health. For more information, see the memorandum

Comments: No Comments

Be Our Guest at the Food Safety Consortium

On behalf of our team, Kestrel Management would like to invite you to attend the 6th Annual Food Safety Consortium Conference & Expo on Nov. 13-15 in Schaumburg, IL.

The Consortium is a premiere event for food safety education and networking—and we want to offer you the chance to visit us at the event (booth #119) for a discounted rate (see offer below).

You can accomplish more in two or three days at the Food Safety Consortium than you might otherwise achieve in weeks! Here are five ways the Food Safety Consortium will allow you to enhance your business:

- Get expert advice on specific challenges faced by your business.

- Listen to insights from thought leaders & innovators.

- Stay up-to-date with emerging or changing trends.

- Upgrade your skills, knowledge and on-the-job effectiveness.

- Gain new ideas and insights to grow your business.

Come see Kestrel at booth #119. When you register, use our discount code Cubs and receive a 20% discount off registration.

Our team is proud to be part of the Food Safety Consortium and hope to see you there!

Comments: No Comments

The Four “A’s” of Food Defense

When looking at FSMA, it’s important to look at what we should be doing in industry under FSMA’s prevention scheme. FDA seeks for companies to assess risk and implement preventive controls on a broad basis. Thinking about risk-based strategies, whether in the supply chain, internal systems, or whether you are a grower or an importer, is key for any food company when planning for the future.

From Reactive to Proactive

With the FSMA rules, FDA has moved from reactive to proactive. Preventive strategies are the essence of FSMA. Proactively creating or updating a food defense and safety plan is the first step to ensure compliance.

The four “A’s” of food defense, as outlined below, provide a methodology for building a proactive and comprehensive food defense program.

Step 1: Assess

Assess the risks throughout the supply chain, including to the origin of raw materials. Conduct a vulnerability assessment of weaknesses and critical control points to identify where someone could attempt product adulteration. The focus must be both inside and outside of company walls and extend to the source of materials and services within the supply chain for producers and distributors of food to the public.

Step 2: Access

Who has access to critical control points and food material risk areas? Pay close attention to the four key activity types that FDA has identified as particularly vulnerable to adulteration:

- Mixing and grinding activities that involve a high volume of food with a high potential for uniform mixing of a contaminant

- Ingredient handling with open access to the product stream

- Bulk liquid receiving and loading

- Liquid storage and handling, which is typically located in remote, isolated areas

Restrict access to these areas from suppliers, contractors, visitors, and most employees—limiting access to critical employees only. This provides a higher level of protection, and supports video and/or physical monitoring.

Step 3: Alerts

Alerts of intentional and unintentional food adulteration must be sent to the appropriate individuals, according to the documented food safety and defense program. Response time is critical. Every passing minute is a minute when more health risks could develop, leading to a greater chance of negative impacts on public safety and the related businesses.

Step 4: Audit

Auditing operational and regulatory compliance helps to ensure and maintain best food defense practices and provide documentation of compliance to regulators. FSMA promotes the safety of the U.S. food supply by focusing on prevention, rather than reactive response. Prevention is only as effective as the actual compliance processes put in place. Regular and random auditing, including remote video monitoring, provides evidence confirming that the appropriate preventive measures are taken and effective.

Taking a proactive approach to food defense that follows these four “A’s” will help meet a key requirement by ensuring that the organization is working to avoid the risks associated with food adulteration and contamination.

Comments: No Comments

Court Orders EPA to Implement RMP Rule

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit ruled on Friday, September 21, 2018 that the EPA must implement the Obama-era Risk Management Plan (RMP) Rule. This comes on the heels of the Court’s ruling on August 17, 2018, which stated that EPA does not have authority to delay final rules for the purpose of reconsideration. Usually, the Court would allow 52 days for the EPA to consider appealing the order and to plan how to implement the rule; however, groups supporting the regulation argued that it can’t wait.

Read more about the currently Court ruling.

USTR Finalizes China 301 List 3 Tariffs

On Monday, September 17, 2018, the Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR) released a list of approximately $200 billion worth of Chinese imports, including hundreds of chemicals, that will be subject to additional tariffs. The additional tariffs will be effective starting September 24, 2018, and initially will be in the amount of 10 percent. Starting January 1, 2019, the level of the additional tariffs will increase to 25 percent.

In the final list, the administration also removed nearly 300 items, but the Administration did not provide a specific list of products excluded. Included among the products removed from the proposed list are certain consumer electronics products, such as smart watches and Bluetooth devices; certain chemical inputs for manufactured goods, textiles and agriculture; certain health and safety products such as bicycle helmets, and child safety furniture such as car seats and playpens.

Individual companies may want to review the list to determine the status of Harmonized Tariff Schedule (HTS) codes of interest.

NACD Responsible Distribution Cybersecurity Webinar

Join the National Association of Chemical Distributors (NACD) and Kestrel Principal Evan Fitzgerald for a free webinar on Responsible Distribution Code XIII. We will be taking a deeper dive into Code XIII.D., which focuses on cybersecurity and information. Find out ways to protect your company from this constantly evolving threat.

NACD Responsible Distribution Webinar

Code XIII & Cybersecurity Breaches

Thursday, September 20, 2018

12:00 -1:00 p.m. (EDT)