Comments: No Comments

Process Safety and Human Performance Reliability

On August 6, 2012, the release of flammable vapor led to a fire at the Chevron Refinery in Richmond, California. That event generated significant public concern about refinery safety and emergency response in California. It also eventually prompted California’s Department of Industrial Relations (DIR) to develop a draft regulatory proposal for a new Cal/OSHA Process Safety Management (PSM) standard that strengthens regulatory oversight, policy, and enforcement. The PSM for petroleum refineries notice hit the California Register on Friday, July 15, 2016.

But California refineries are not alone. Federal changes are on the way, as well, as OSHA considers revisions to its PSM standard.

Proposed Cal/OSHA Process Safety Management (PSM) Standard Changes

As a recap, the proposed Cal/OSHA PSM changes modify existing PSM language and introduce a number of new management system elements and other requirements. These amendments require California refineries to commit to the following:

- Use the Hierarchy of Hazard Controls to choose safer, more enduring technologies that address safety concerns and help to eliminate or minimize hazards in refinery processes.

- Perform damage mechanism reviews to assess physical degradation, such as corrosion and mechanical wear, and to determine recommended corrective actions.

- Conduct safeguard protection analysis to ensure that safeguards will help prevent initiating events from turning into major catastrophes.

- Implement corrective actions with clear and enforceable deadlines and consequences for inaction to ensure that safety program improvements are carried out.

- Implement appropriate Management of Change (MOC) activities so safety is factored into changes to operations, maintenance procedures, personnel, etc., all of which can undermine plant safety.

- Perform periodic safety culture assessments to evaluate management’s and employees’ attitudes, perceptions, and values as they pertain to safety.

- Account for human factors (e.g., training and competency levels, fatigue, experience, communication, physical challenges), which can greatly influence accidents and incidents in the workplace.

- Conduct root cause analysis to identify underlying causes of the incident and recommended corrective actions to help prevent recurrence.

- Engage employees at all levels in all elements of the PSM program, including working to prevent accidents and incidents through the means described above.

The Human Element of PSM

Employee and contractor performance is a significant source of risk within any organization. The majority of accidents and other unintended events are—at least in part—the result of human error. It is not surprising that Cal/OSHA’s proposed PSM regulations and potential Federal PSM changes recognize the importance of the “human element” in a number of the changes—from performing safety culture assessments to account for human factors, to engaging employees.

Many companies struggle with the following challenges as they work to establish and/or improve elements of their PSM programs:

- How do we identify factors contributing to incidents?

- What are appropriate recommendations that will drive improvements?

- How should we include human factors in Process Hazard Analyses (PHAs)?

- How can we improve our safety culture?

Often, these elements are treated independently, but this overlooks the important relationship between them. For example, any unintended event (e.g., an LOPS, process upset, safety incident) is the result of multiple contributing factors, not a single event. Focusing on these contributing factors enables companies to develop a deeper understanding of why incidents are occurring. Linking contributing factors to specific barriers further allow companies to identify weaknesses in their processes and procedures and to develop appropriate recommendations to drive improvements. Conducting contributing factor analyses also enables the company to identify specific human factors to be used in their PHAs.

Human Performance Reliability (HPR) Approach

Kestrel’s Human Performance Reliability (HPR) approach provides an integrated solution for addressing new PSM requirements. Unlike a typical root cause analysis, which addresses factors leading to a specific incident, HPR is based on a sophisticated statistical analysis of human factor data obtained from multiple incidents. This allows companies to identify and access broader—and potentially systemic—issues that are affecting the safety performance of the organization.

HPR consists of three elements:

- Incident Investigation and Analysis (IIA) – IIA adopts the framework provided by the Human Factors Analysis and Classification System (HFACS) to classify human error and other contributing factors—but with the additional step of associating the control(s) that failed to prevent the incident from occurring. Statistical analyses help to identify patterns in the data to pinpoint the human errors and controls that are appearing most frequently.

- Procedure Improvements – Although the IIA process will identify where improvements are needed (i.e., which controls are associated with incidents), it will not result in improved safety performance—not without completing associated improvement projects. Only by scoping and implementing those improvement projects will companies realize improved safety performance.

- Safety Culture Assessment – Learning organizations actively seek the underlying causes of incidents and use data to make performance improvements. These organizations typically have robust systems to ensure that the traits that represent a strong safety culture are in place, mature, and fully integrated into standard practices

While the individual elements can be very helpful to a company, deploying them in tandem provides the richest and most comprehensive benefit to overall safety performance. That is because the three components are inherently complementary; each improves the effectiveness of the others.

Systemic Improvements

This process provides immediate value when applied to the investigation of an individual event by identifying additional factors that may have been missed following a traditional root cause analysis approach. It is most powerful, however, when data from multiple events are aggregated. The results of multiple investigations yield a pattern of human factor indicators that can be used to uncover system opportunities for PSM and operational enhancements and overall improved reliability.

Comments: No Comments

California PSM Standards: Targeting Refinery Safety

On August 6, 2012, a release of flammable vapor led to a fire at the Chevron Refinery in Richmond, California. That event generated significant public concern about refinery safety and emergency response in California. It also prompted the California Governor’s report, “Improving Public and Worker Safety at Oil Refineries,” the formation of the Interagency Refinery Task Force (IRTF), and, eventually, the proposed regulatory changes to specifically target refinery safety.

Proposed Cal/OSHA Process Safety Management (PSM) Standard Changes

As most California refineries are aware, California’s Department of Industrial Relations (DIR) developed a draft regulatory proposal for a new Cal/OSHA Process Safety Management (PSM) standard to strengthen regulatory oversight, policy, and enforcement. The PSM for petroleum refineries notice hit the California Register on Friday, July 15, 2016—and Federal changes are on the way, as well, as OSHA considers revisions to its PSM standard.

As a recap, the proposed Cal/OSHA PSM changes modify existing PSM language and introduce a number of new management system elements and other requirements. These amendments require California refineries to commit to the following:

- Use the Hierarchy of Hazard Controls to choose safer, more enduring technologies that address safety concerns and help to eliminate or minimize hazards in refinery processes.

- Perform damage mechanism reviews to assess physical degradation, such as corrosion and mechanical wear, and to determine recommended corrective actions.

- Conduct safeguard protection analysis to ensure that safeguards will help prevent initiating events from turning into major catastrophes.

- Implement corrective actions with clear and enforceable deadlines and consequences for inaction to ensure that safety program improvements are carried out.

- Implement appropriate Management of Change (MOC) activities so safety is factored into changes to operations, maintenance procedures, personnel, etc., all of which can undermine plant safety.

- Perform periodic safety culture assessments to evaluate management’s and employees’ attitudes, perceptions, and values as they pertain to safety.

- Account for human factors (e.g., training and competency levels, fatigue, experience, communication, physical challenges), which can greatly influence accidents and incidents in the workplace.

- Conduct root cause analysis to identify underlying causes of the incident and recommended corrective actions to help prevent recurrence.

- Engage employees at all levels in all elements of the PSM program, including working to prevent accidents and incidents through the means described above.

The Human Element of PSM

Employee and contractor performance is a significant source of risk within any organization. The majority of accidents and other unintended events are—at least in part—the result of human error. It is not surprising that Cal/OSHA’s proposed PSM regulations recognize the importance of the “human element” in a number of the proposed changes—from performing safety culture assessments, to account for human factors, to engaging employees.

Kestrel works with many refining and petrochemical companies that are in the process of establishing and/or improving elements of their PSM programs. Over the years, we have seen many of our clients struggle with the following challenges:

- How do we identify factors contributing to incidents?

- What are appropriate recommendations that will drive improvements?

- How should we include human factors in Process Hazard Analyses (PHAs)?

- How can we improve our safety culture?

Often, these elements are treated independently, but we have found that this overlooks the important relationship between them. For example, any unintended event (e.g., an LOPS, process upset, safety incident) is the result of multiple contributing factors, not a single event. Focusing on these contributing factors enables companies to develop a deeper understanding of why incidents are occurring. Linking contributing factors to specific barriers further allow companies to identify weaknesses in their procedures and processes and to develop appropriate recommendations to drive improvements. Conducting contributing factor analyses also enables the company to identify specific human factors to be used in their PHAs.

Human Performance Reliability (HPR) Approach

Kestrel’s Human Performance Reliability (HPR) approach provides an integrated solution for addressing the new PSM requirements, as outlined above. Unlike a typical root cause analysis, which addresses factors leading to a specific incident, HPR is based on a sophisticated statistical analysis of human factor data obtained from multiple incidents. This allows companies to identify and access broader—and potentially systemic—issues that are affecting the safety performance of the organization.

HPR consists of three elements:

- Incident Investigation and Analysis (IIA) – IIA adopts the framework provided by the Human Factors Analysis and Classification System (HFACS) to classify human error and other contributing factors—but with the additional step of associating the control(s) that failed to prevent the incident from occurring. Statistical analyses help to identify patterns in the data to pinpoint the human errors and controls that are appearing most frequently.

- Procedure Improvements – Although the IIA process will identify where improvements are needed (i.e., which controls are associated with incidents), it will not result in performance improvements—not without completing associated improvement projects. As part of our HPR services, Kestrel works with clients to scope and implement those improvement projects that will lead to improved safety performance.

- Safety Culture Assessment – Learning organizations actively seek the underlying causes of incidents and use data to make performance improvements. These organizations typically have robust systems to ensure that the traits that represent a strong safety culture are in place, mature, and fully integrated into standard practices.

While the individual elements can be very helpful to a company, deploying them in tandem provides the richest and most comprehensive benefit to overall safety performance. That is because the three components are inherently complementary; each improves the effectiveness of the others.

Systemic Improvements

The HPR process provides immediate value when applied to the investigation of an individual event by identifying additional factors that may have been missed following a traditional root cause analysis approach. It is most powerful, however, when data from multiple events are aggregated. The results of multiple investigations yield a pattern of human factor indicators that can be used to uncover system opportunities for PSM and operational enhancements and overall improved reliability.

Experienced Professionals

Kestrel has experienced PSM and HPR professionals on our team, who have successfully developed programs, completed deployments, and conducted training in the refining and petrochemical industries. As California refineries prepare for significant PSM regulatory changes, we would welcome the opportunity to discuss how we can help you manage your PSM requirements and improve your overall safety performance.

Environment / Quality / Safety

Comments: No Comments

Management System Internal Audit: What to Expect

Many companies face requirements to conduct management system internal audits. And many probably consider it to be one of those “necessary evils” of doing business. In reality, an internal audit can be a great opportunity to uncover issues and resolve them before an external audit begins. An internal audit can sometimes even enable more improvements than an external audit because it allows the company to review processes more often and more thoroughly. So what, exactly, goes into an internal audit?

What Is an Audit?

First, conducting a management system internal audit encompasses all of the efforts to gather, accumulate, arrange, and evaluate data so that there is sufficient information to arrive at an audit opinion. According to the ANSI/ASQC Standard Q1-1986 Generic Guidelines for Auditing Management Systems, an audit is:

a systematic examination of the acts and decisions by people with respect to Q/EHS issues, in order to independently verify or evaluate and report conformance to the operational requirements of the program or the specification or contract requirement of the product or service.

Internal audits should be carried out to look for areas for improvement and best practices. In an internal audit, the auditor is evaluating, verifying, and reporting conformance or non-conformance in terms of related documentation. The auditor assesses systems, processes, and products against the related documentation:

- Systems are compared against company directives and requirements.

- Processes are compared against procedures, process charts, and work instructions.

The auditor examines where and how “operational requirements of the management system” are described. This is done by reviewing each policy, procedure, work instruction, checklist, and form looking for each “actionable item” listed within.

The Interview

The auditor will go out into the workforce and ask the prepared questions to various employees. Based on the responses given, the auditor may need to ask follow-up questions to get a clear understanding of how an operation works. Questions asked by auditors are generally open-ended to give the auditee the opportunity to elaborate. The auditor’s goal is to give the employee the opportunity to think prior to answering and to follow the audit trail wherever it leads—within or outside of the department.

Tangible Evidence

In order for an internal audit to support improvement steps, the auditor will seek tangible evidence. For example, work instructions require that inspections are completed every day, but the checklist shows that no checks have been performed for the last week. Tangible evidence may include taking a photo copy of the checklist to document this issue.

Evaluating Internal Controls

During the audit, the auditor is looking for internal controls that regulate an operation. There are seven steps in evaluating internal controls:

- Observe the Operation: The auditor needs to understand what processes and systems to review, where they are located, and who is responsible for them.

- Identify Constraints: The auditor will identify constraints to the extent possible, such as:

- Scattered information

- Internal opposition

- Process not capable

- Process not in control

- Unavailable information

- Evaluate Risk: The auditor will assess the importance and risk of internal controls not detecting and preventing non-conformances. The auditor will ask personnel being audited and management if there is anything more that could be done to identify and control risk.

- Evaluate the Internal Control Structure: Usually extensive internal controls exist, operate properly, and maintain/improve the process; however, this may not be an accurate assumption. Controls may not exist, may be weak, or may control and measure unimportant variables. It is very important for the auditor to resist assuming that the way an existing system has been set up is the correct way to do something. Auditors should challenge how and why something is being done to encourage system improvements.

- Test the Effectiveness of the Internal Control Structure: Gathering evidence is the process of collecting data and information critical to support a decision or judgment rendered by the auditor.

- Evaluate Evidence: Once evidence has been gathered from interviews, observations, or records, the auditor must distill and summarize the data into useful information for the company. The evidence is then reviewed to determine whether systems and controls are working effectively.

- Issue an Opinion: When all is said and done, the auditor must issue an opinion of conformance or non-conformance. In a deficiency finding (non-conformance), the audit report will clearly state that there is a variance between what is and what should be. All evidence findings should be listed to support this conclusion.

Clarify Issues and Non-Conformances

Upon completion of an audit, there may be times when clarification of an issue or concern will be warranted. This is when the auditor may go back to the department head and review the current understanding of the audit results. The department head should have ample time to discuss and clarify any issues of concern.

Any outstanding issues that warrant a non-conformance report should be discussed to ensure that the company understands: 1.) why the issue is considered a non-conformance, and 2.) what may need to be done to rectify the situation. It is important to also discuss all positive findings from the audit to leverage best practices.

By using an internal audit to actually improve operations—and not just as another requirement to fulfill—companies can realize significant value through:

- Meeting regulatory/certification requirements prior to the external audit

- Improving operational controls and processes

- Enhancing overall management system effectiveness

Comments: 3 Comments

12 Steps to HACCP Implementation

Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points (HACCP) is a process control system designed to identify and prevent microbial and other hazards in food production. The HACCP system is used at all stages of the food chain, from food production to packaging and distribution.

HACCP includes steps designed to identify food safety risks, prevent food safety hazards before they occur, and address legal compliance. The most important aspect of HACCP is that it is a preventive system rather than an inspection system of controlling food safety hazards. Prevention of hazards cannot be accomplished by end product inspection. Controlling the production process with HACCP offers the best approach.

Breaking It Down

Kestrel follows twelve steps to help ensure the successful implementation and integration of HACCP throughout a company:

- Assemble a HACCP team with the appropriate product-specific knowledge and expertise to develop an effective Food Safety Plan. The team should comprise individuals familiar with all aspects of the production process, plus specialists with expertise in specific areas, such as engineering or microbiology. It may be necessary to use external sources of expertise in some cases.

- Describe the product in full detail, including composition, physical/chemical structure, microcidal/static treatments, packaging, storage conditions, and distribution methods.

- Identify the intended/expected use of the product by the end user. It is also important to identify the consumer target groups. Vulnerable groups, such as children or the elderly, may need to be considered specifically.

- Construct a flow diagram that provides an accurate representation of each step in the manufacturing process—from raw materials to end product—and may include details of the factory and equipment layout, ingredient specifications, features of equipment design, time/temperature data, cleaning and hygiene procedures, and storage conditions.

- Perform an on-site confirmation of the flow diagram to confirm that it is aligned with actual operations. The operation should be observed at each stage and any discrepancies between the diagram and normal practice should be recorded and amended. It is essential that the flow diagram is accurate since the hazard analysis and identification of Critical Control Points (CCPs) rely on the data it contains.

- Conduct a hazard analysis for each process step to identify any biological, chemical, or physical hazards. This assessment also includes rating the hazard using a risk matrix, determining if the hazard is likely to occur, and identifying the preventive controls for the process step.

- Determine Critical Control Points (CCPs)—those areas where previously identified hazards may be eliminated. The final HACCP Plan will focus on the control and monitoring of the process at these points.

- Establish critical limits and develop processes that limit risk at CCPs. More than one critical limit may be defined for a single step. Criteria used to set critical limits must be measurable and include rating and ranking of hazards for each step of the flowchart.

- Monitor CCPs and develop processes for ensuring that critical limits are followed. Monitoring procedures must be able to detect loss of control at the CCP and should provide this information in time to make appropriate adjustments so that control of the process is regained before critical limits are exceeded. Where possible, process adjustments should be made when monitoring results indicate a trend towards a loss of control at a CCP.

- Establish preplanned corrective actions to be taken for each CCP in the HACCP plan that can then be applied when the CCP is not under control. If monitoring indicates a deviation from the critical limits for a CCP, action (e.g., proper isolation and disposition of affected product) must be taken that will bring it back under control.

- Establish procedures for verification to determine whether the HACCP system is working correctly. Verification procedures should include detailed reviews of all aspects of the HACCP system and its records. The documentation should confirm that CCPs are under control and should also indicate the nature and extent of any deviations from the critical limits and the corrective actions taken in each case.

- Establish proper documentation and recordkeeping for all HACCP processes to ensure that the business can verify that controls are in place and are being properly maintained.

Developing and implementing a HACCP program requires a significant investment of time and effort. Though HACCP continues to evolve, it is up to the company to design and customize HACCP programs to make them effective and workable. These twelve steps break HACCP into manageable chunks and will help ensure that the company is consistently and reliably producing safe food that will not cause harm to the consumer.

Comments: 1 Comment

Hazardous Materials Management Plan (HMMP)

An ever-growing area of concern across the industry is the appropriate management of hazardous materials and waste. The number of government regulations concerning hazardous materials handling alone is significant—from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) and Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), to the Department of Transportation (DOT), Department of Homeland Security (DHS), Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA), and Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC). Under these laws, the disposal of hazardous material in the sewer system, stormwater system, on the ground, or in regular trash is regulated by a number of prohibitions.

In addition to these regulations, there are international codes for hazardous materials —developed by the International Fire Code (IFC)/International Building Code (IBC) and operationalized by local officials—that apply across the industry. Kestrel has found that more and more facilities, particularly those in retail warehousing, are being subjected to the requirements of these codes.

IFC/IBC Requirements

Local fire marshals have the responsibility to inspect facilities and ensure that hazardous materials are properly managed and stored. Although local requirements may vary, most local laws have closely adopted the IFC/IBC requirements for hazardous materials management.

The IFC/IBC requirements reference hazardous material as it relates to hazard classes—a significant difference compared to some of the other hazardous materials regulations across the U.S. Applicability and specific requirements are based on:

- Hazard class of the chemical

- Volume of the chemical

- How the chemical is used

- How the chemical is stored

- Building occupancy

Depending on these things, the local fire marshal may require the facility to develop a Hazardous Materials Management Plan (HMMP), conduct a Hazardous Materials Inventory, and/or submit a Hazardous Materials Permit.

HMMP Requirements

The purpose of a Hazardous Materials Management Plan (HMMP) is to describe the company’s procedures for storing, using, managing, and disposing of hazardous materials in a safe manner.

The information requested for an HMMP is different than that required for Tier II reporting under Section 312 of the Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act (EPCRA). The purpose of the Tier II form is to provide state and local officials and the public with information on the general hazard types and locations of hazardous chemicals at the facility.

Notable differences between Tier II and HMMP include the following:

- Classifications and regulations are different.

- Volumes that trigger an HMMP are much lower.

- Use and storage of the chemical, as well as the occupancy of the building, influence the requirements for an HMMP.

Beyond the HMMP, a company may need to conduct a Hazardous Materials Inventory, which requires defining hazard classes for chemicals at the facility and may need to apply for a Hazardous Material Permit under the authority of the local fire marshal.

While there may be variations by the local authority, in general, the Plan and Inventory include the following:

| Hazardous Materials Management Plan (HMMP) | Hazardous Materials Inventory |

|

|

Hazard Classes and MAQs

Hazard classes, as required in the Hazardous Materials Inventory, are listed in IFC Appendix E. They include physical hazards and health hazards, and typically have a number of associated subcategories. A hazard class is not listed on a Safety Data Sheet (SDS). The classes include:

- Explosives

- Compressed Gases

- Flammable and combustible liquids

- Flammable solids

- Combustible dust and powders

- Oxidizers

- Organic Peroxides

- Pyrophoric materials

- Unstable materials

- Water reactive materials

- Cryogenic materials

- Toxic materials

- Corrosives

The MAQ for a hazardous material will determine occupancy requirements and required controls (sprinkler systems, temperature controlled storage etc.). The MAQs are located in:

- IBC Table 307.1(1) and IFC Table 5003.1.1(1) for physical hazard hazardous materials

- IBC Table 307.1(2) and IFC Table 5003.1.1(2) for health hazard hazardous materials

- IFC Tables 5003.1.1(3) and (4) for outdoor control area MAQ

Note that the IBC and IFC are both involved to determine the hazard classification and the associated storage limits and requirements.

Moving Forward

Companies with hazardous materials must manage their hazardous materials safely. To ensure that they are meeting the IFC/IBC requirements, it is beneficial for companies to:

- Check with the local fire marshal to determine what needs to be done to meet local requirements, including engineering design requirements.

- Prepare and maintain a facility map identifying storage areas, sprinkler systems, emergency plans, etc. and document it in an HMMP.

- Contact vendors/installers of sprinkler systems and other equipment to ensure that the systems are designed for their intended use. The installer is a good resource for what would be allowed in a particular area and what the limitations of the system might be. This should be verified by qualified engineers.

- Conduct a Hazardous Materials Inventory, if required, to define hazard classes. This may require outside assistance to appropriately classify chemicals.

- Complete any special Hazardous Materials Permits, if required.

- Comply with the conditions of a Permit and with the technical specifications for activities such as maintenance; recognize and manage any changed conditions.

- Regularly inspect and audit the systems for compliance.

Managing hazardous materials is a part of doing business safely. Satisfying local fire marshal requirements will further help ensure that the company, the environment, and the surrounding community remain unharmed.

Comments: No Comments

Reducing Human Error in Process Safety Short Course

Human error is a significant source of risk within any organization. Management uses a variety of operational controls and barriers, including policies, procedures, work instructions, employee selection and training, auditing, etc., to reduce the likelihood of human error. Accidents occur when there is a failure in one or more of these controls and/or barriers.

Many companies are working to reduce their incident rates by integrating a more detailed analysis of human factors into their incident investigation procedures. In doing so, companies can identify weaknesses in their operational controls at a specific job site, within an operating region, and across the organization.

Reducing Human Error in Process Safety

Join Kestrel and Texas A&M’s Mary Kay O’Connor Process Safety Center this summer for a continuing education short course that provides an opportunity for companies to learn more about integrating human factor data into incident investigations and identifying those operational controls that need improvement.

Reducing Human Error in Process Safety

July 7, 2016

Instructors: A.W. Armstrong and Will Brokaw, Kestrel Management

Location: Phoenix Contact Customer Technology Center

Houston, TX

Credit: 0.7 CEUs/7 PDHs

Register online

What You’ll Learn

This course will outline a process that companies can use to integrate human factor data into incident investigations and identify operational controls that need improvement. Attendees will also get a general overview of human factors and strategies for reducing error in operations.

Who Should Attend

Process safety management coordinators, risk management planning coordinators, and new health, safety, and environment auditors.

Pull vs. Push Reporting: Leading KPI Development

Key performance indicator (KPI) is, arguably, one of the biggest buzzwords of the decade. If you want someone’s attention, mention KPIs. According to Investopedia, KPIs are “a set of quantifiable measures that a company or industry uses to gauge or compare performance in terms of meeting their strategic and operational goals.”

For some individual practices—financials, inventory, sales—KPIs are relatively standard. For example, a company may measure revenue growth year after year as a standard KPI. As we bridge into operational practices with varying numbers of employees and levels of risk, however, it can become more difficult to understand not only how to establish KPIs but also where to get the data.

Technology can help to create a pull-to-push methodology that puts site-specific leading KPIs at stakeholders’ fingertips.

Leading vs. Lagging Indicators

In order to understand how to use this pull-to-push methodology to create leading KPIs, it is important to first understand the concept of leading versus lagging indicators.

- Lagging indicators measure and help track how the company is performing in comparison to its goals. Lagging indicators are usually fairly easy to measure—but they can be hard to influence because what they are measuring has already happened or performance data already captured. In this way, lagging indicators are backward-focused. Many standard performance metrics are lagging. In safety, for example, the Recordable Incident Rate is a lagging indicator. Important information to know but hard to change.

- Leading indicators signify the direction performance is going. Because leading indicators come before a trend, they are often seen as business drivers and should be incorporated into the business strategy. The forward-looking nature of leading indicators may make them harder to measure and they may change quickly; however, leading indicators are generally easier to influence. A good example of a leading indicator in determining the most common causes of an incident before it happens to prevent future recurrence, thereby impacting performance.

Pull vs. Push Metrics

That brings us back to the pull-to-push methodology. Or, in essence, digging for metrics versus having KPIs sent directly to the appropriate stakeholders.

With a push approach, metrics are literally “pushed” to end-users, who then extract meaningful insights and take appropriate actions for themselves. Push metrics can have a number of components that trigger when (and who) metrics are sent to, including threshold, capacity, severity, and timing.

Conversely, with a pull approach, data is pulled in order to answer specific business questions. Pull metrics generally require someone with analytical skills to dig deeper into the data to identify the desired metrics.

While pull metrics may be more time consuming to identify and obtain, that doesn’t mean pull metrics aren’t important to have. In fact, organizations often need to pull data in order to create the push metrics that provide for standard KPIs. And push metrics may demand you circle back and pull further information. In reality, the process is cyclical: pull produces what should be pushed; push cycles back to pull in order to dig deeper into the details.

Creating Standard KPIs

How does an organization, then, get to the point of having standard KPIs that can be pushed when needed and that don’t require the time and investment associated with digging for information?

Technology can help to create that pull-to-push methodology for creating standard KPIs. This requires a number of things:

- The program must be well-established and designed with the operational requirements, capacity, tools, and skills to effectively integrate the program itself and associated data with technology.

- Assuming a program such as this is developed, initial reports can be pulled to check the program’s effectiveness based on a number of key attributes/metrics. This yields analyzable data.

- This data should be explored in many different ways. This allows the company to start seeing the interaction between stakeholders and the data and, eventually, creates the “a-ha” moment of understanding as to what metrics are important and meaningful.

- At this point, it becomes possible to begin comparing data and metrics on a periodic basis, while continuing to pull information from technology. Remembering what queries are effective will aid in establishing initial leading KPIs. This process also will yield improved understanding of how the data gathering process (e.g., incident investigation) needs to be improved and standardized for a more reliable pull of information.

- This comparison of data should then be used to discover what data is beneficial and what information needs to be more granular to really hone in on the standard KPI.

Walking through this process and leveraging available technology makes it possible to effectively transition from pull methodology to push reporting—putting leading KPIs in the hands of decision-makers and identified stakeholders.

Comments: No Comments

Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA) Rules Update

The FDA Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA) originated in the mid-2000s when approximately 48 million people were getting sick, 128,000 were hospitalized, and 3,000 died annually from foodborne diseases, according to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC). This resulted in a significant public health burden that is largely preventable.

Signed into law by President Obama on January 4, 2011, FSMA aims to ensure that the food supply is safe—from responding to contamination to preventing it. The Act represents the most sweeping reform of our food safety laws in more than 70 years.

New Rulemaking

Since its passage, food-related industries have been waiting for a number of new rules to be published under FSMA. The new rules being published for enforcement will complement the existing rules in place prior to 2011 and rules that were enforceable at the signing of FSMA, including meeting all of the established requirements under 21 CFR Section 110. These include Inspection of Records; Registration of Food Facilities; FDA Performance Standards; and Authority to Collect Fees, Mandatory Recall Authority, and Administrative Detention.

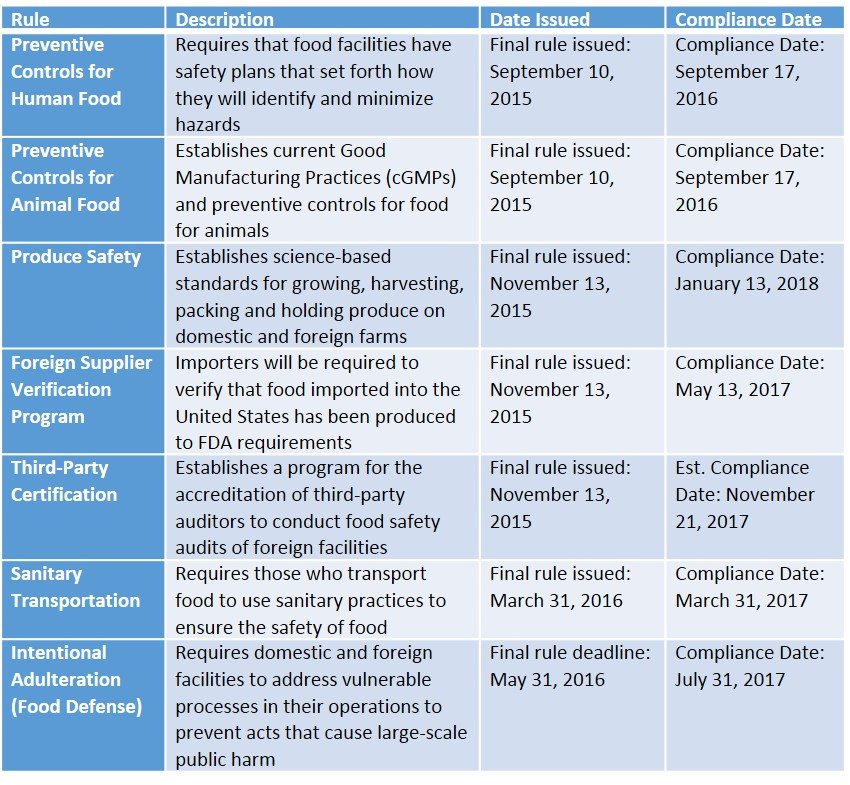

After numerous delays in rulemaking, court-ordered deadlines for finalizing and publishing seven foundational new rules were established for 2015/2016. Not surprisingly, the FDA declared 2015 “the year of FSMA” at their FSMA Kickoff Meeting for industry stakeholders on April 23, 2015. The new rules include the following final and pending dates:

*Later dates or applicability may be provided for very small companies

**Dates may be subject to change

***cGMP refers to Current GMPs under FSMA or ones that are current and updated within the past two years

Enforcement

With these new FSMA rules, all issues related to the processing and distribution of safe food will be enforceable by the FDA. This broad authority includes the use of other agencies for enforcement and eliminates the need for the FDA to require judicial approval for investigations, access to information, issuing recalls, ordering the detention of product, suspending business registrations, levying fines, and controlling the food supply chain to ensure the safety of food for the public.

Compliance Requirements

Establishing the rulemaking deadlines is the first step toward implementing the law. Compliance dates—up to one year or longer after publication—require companies to then develop the appropriate programs to meet FDA Guidance Documents pending release. These Guidance Documents are intended to assist industry in program development; however, there is little confidence that these will be issued in a timely manner. Thus, with compliance commencing by September, companies must establish their own programs and use Guidance Documents for eventual comparison.

As the new FSMA rules are published, companies must determine their compliance requirements to ensure the distribution of only pure and unadulterated food product. Each company must assess all aspects of FSMA to first determine which rules are specific to them, their business, and their supply chain and, second, how to best comply. This is challenging, as these programs will be new and not previously tested for compliance. A gap assessment will help companies determine requirements and then develop the required compliance programs by the established dates.

Food Defense and Safety Plan

There is one common need across all FSMA rules that companies should consider: proactively creating a Food Defense and Safety Plan—or updating a current one. Taking a proactive approach to food defense will not only make FSMA adherence less daunting for organizations, but it will also ensure that they are working to avoid the risks associated with food adulteration and contamination.

This also aligns with other existing laws already in place, as site food defense is an imperative required by other laws. Security programs must be established if they are not already implemented. FSMA rules include one against deliberate contamination of food. The FDA and other authorized agencies will look to see if programs are established and that the company has assessed risks, controls access, has an alert system, and has an audit program that is functioning to plan.

Companies must take action to include these within their Food Defense and Safety Plan:

- Ensure the building, premises, and processes meet existing physical and defense requirements

- Verify employees understand the company’s FDA/FSMA requirements with visible evidence

- Assess and audit the written Food Safety Plans and look for gaps/areas to close

- Ensure the integrity of the internal audit program to FDA/FSMA and food safety requirements

- Confirm that the company is prepared to provide documentation in 24 hours if requested by the FDA

- Ensure that all suppliers and indemnity are effectively tracked, monitored, and evaluated

- Prove traceability and maintain a mock recall program for any recall circumstance

Food Safety Management System (FSMS)

Based on the complexity and broad nature of the FSMA rules, it is also recommended that companies move forward with updates to their Food Safety Management Systems (FSMS), which can be adjusted when the final rules are issued. Certification to one of the Global Food Safety Initiative’s (GFSI) benchmarked standards provides some level of compliance, including security and defense.

Preventive Controls

Preventive controls require a final processor or distributor to ensure that the supply chain has effective programs. Preventive controls must go back to the origin of each material. Ultimately, all food ingredients and materials must be included to meet preventive control requirements.

FDA seeks for companies to assess risks and implement preventive controls in their supply chain. For this, companies must understand where the risks are and if appropriate controls are implemented. A key issue to consider is how regulators and suppliers have different senses of what appropriate controls really are for this important goal of FSMA.

Qualified Individuals

Another key aspect of FSMA and a change to past FDA requirements is to establish and maintain Qualified Individuals and Food Safety Lead/Teams to ensure that each location’s food safety system is adequately managed. Key requirements include the following:

- Identify a qualified lead food site operator at all times

- Be ready for an inspection with a well-scripted inspection program

- Keep the communication list within the company current, including regulatory service providers

- Food Safety Lead must be present during food operations for release of safe food

- Qualified back-ups must be established for the primary Food Safety Qualified Individual or Lead

Actions to Take

Any company that produces or distributes food product or material needs to determine compliance requirements to implement the appropriate FSMA programs. The best method for determining program development needs is to conduct an action-oriented gap assessment of current programs to FSMA requirements. Due to the Act’s complexity, this process should begin well in advance of final compliance dates. If programs are not currently in development, they must be short to avoid the potential of non-compliance to FDA, customers, and the supply chain.

Comments: No Comments

Risk Management Plan (RMP) Changes: Proposed Rule

Since President Obama issued Executive Order (EO) 13650, Improving Chemical Facility Safety and Security, in August 2013, Kestrel has been following the USEPA’s efforts to carry out the EO, specifically as it relates to the Risk Management Plan (RMP) rule.

After extensive information gathering over the past two years, including issuing a Request for Information (RFI) and conducting Small Business Advocacy Review (SBAR) panels, the USEPA announced its proposed revisions to the RMP regulations on February 25, 2016.

Why RMP?

While chemicals are obviously an important part of so many aspects of our lives, improper handling and management can result in catastrophic releases that have severe and lasting impacts—loss of life, injury, property damage, community disruption.

The RMP Rule implements Section 112(r) of the Clean Air Act Amendments, and is aimed at preventing and/or reducing the severity of accidental chemical releases. RMP applies to all stationary sources with processes that contain more than a threshold quantity (TQ) of a regulated substance (based on toxicity, volatility, and flammability criteria). These sources must comply with the RMP regulations by taking defined steps to prevent accidents and by preparing and submitting an RMP to USEPA at least every five years.

Despite the RMP Rule, according to the February 25 USEPA press release referenced above, “While numerous chemical plants are operated safely, in the last 10 years more than 1,500 accidents were reported by RMP facilities. These accidents are responsible for causing nearly 60 deaths, some 17,000 people being injured or seeking medical treatment, almost 500,000 people being evacuated or sheltered-in-place, and costing more than $2 billion in property damages.”

These impacts—amongst other things—reinforce the EO and highlight the importance of modernizing the existing RMP Rule to:

- Improve chemical process safety

- Assist authorities in planning for and responding to accidents

- Improve public awareness of chemical hazards at regulated sources

Proposed Rule

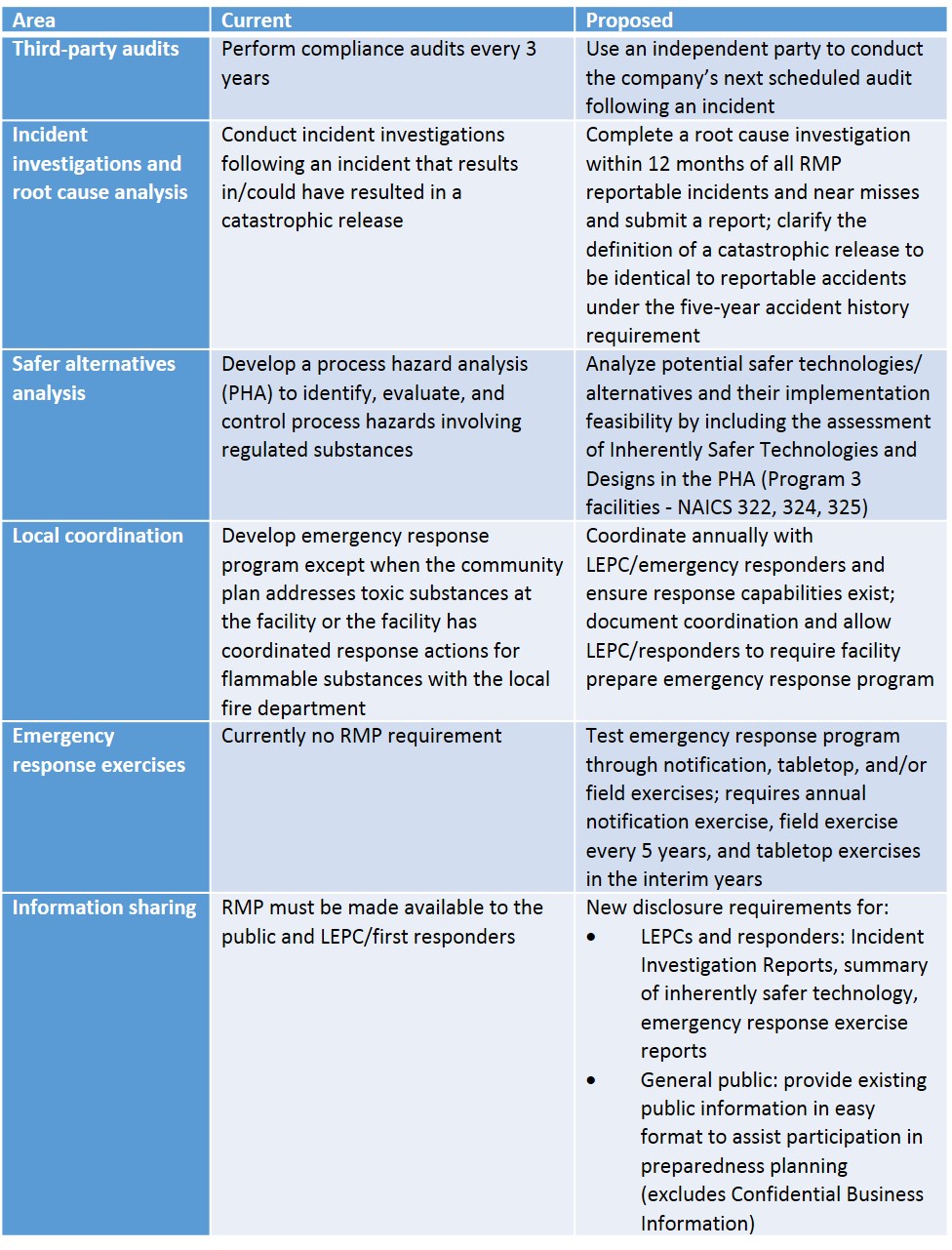

The proposed amendments, as outlined in the table below, are intended to improve the requirements to enhance chemical safety at RMP facilities. Of important note, the USEPA is not proposing any revisions to the list of regulated substances under RMP at this time; however, the Agency may propose additions to this list in a separate action.

Things to Consider

There are a number of alternatives that the USEPA is still considering the proposed changes outlined above. The Agency plans to hold a public meeting to allow stakeholders to comment on the proposed rule; written comments may also be submitted within 60 days after the proposed rule is published in the Federal Register.

In reviewing and commenting on the proposed rule, it is important to consider the following:

- How might the proposed amendments impact your business?

- What additional and/or different criteria for third-party auditors should be required?

- What clarification may be required to effectively coordinate with LEPCs?

- What information is appropriate to share to improve emergency coordination with local responders and the community?

- What issues does your facility foresee with rule compliance?

Again, the proposed changes to the RMP Rule represent just one of the actions that the U.S. government is undertaking to improve chemical safety and security. Kestrel will continue to track these amendments, as well as other actions and decisions that may impact chemical facility operations.

Kestrel Tellevate News / Safety

Comments: No Comments

Kestrel to Present at the AFPM Annual Meeting

Join Kestrel at the AFPM Annual Meeting to hear William Brokaw present his paper, Using a Data-Driven Method of Accident Analysis: A Case Study of the Human Performance Reliability (HPR) Process.

AFPM 2016 Annual Meeting

March 13-15, 2016

Kestrel Presentation: March 14 at 3:30 p.m.

Hilton San Francisco Union Square

San Francisco, CA

The Role of Human Error in Occupational Incidents

The concept of human error and its contribution to occupational accidents and incidents have received considerable research attention in recent years. When an accident/incident occurs, investigation and analysis of the human error that led to the incident often reveals vulnerabilities in an organization’s management system.

This recent emphasis on human error has resulted in an expansion of knowledge related to human error and the most common factors contributing to incidents. Kestrel’s Human Performance Reliability (HPR) process helps to classify human error—with the additional step of associating the control(s) that failed to prevent the incident from occurring. This process allows organizations to identify how and where to focus resources to drive safety performance improvements.

In this presentation, Will describes Kestrel’s method for identifying the most frequent human errors and most problematic controls and presents a case study wherein HPR was applied to a large petroleum refining company.

Catch Up with Kestrel

In addition to the presentation on March 14, Kestrel’s experts will also be on hand throughout the Annual Meeting to talk with you. We welcome the opportunity to learn more about your needs and to discuss how we help our chemical and oil & gas clients manage environmental, safety, and quality risks; improve safety performance, and achieve regulatory compliance assurance