Comments: No Comments

Risk Management Plan (RMP) Final Amendments

Chemicals are an important part of many aspects of our lives; however, improper handling and management of chemicals can result in catastrophic releases that have severe and lasting impacts—loss of life, injury, property damage, community disruption. USEPA’s Risk Management Plan (RMP) data shows that in the last 10 years, there have been more than 1,517 reportable incidents of accidental chemical releases. Those incidents were responsible for 58 deaths, 17,099 injuries, the evacuation or shelter-in-place of almost 500,000 people, and over $2 billion in property damage.

Charting the Changes to RMP

The USEPA’s RMP Rule (Section 112(r) of the Clean Air Act Amendments) is aimed at reducing the frequency and severity of accidental chemical releases. Changes to the RMP Rule have been in progress since former President Obama issued Executive Order (EO) 1365, Improving Chemical Safety and Security, in August 2013. The focus of the EO is to reduce risks associated with hazardous chemicals to owners and operators, workers, and communities by enhancing the safety and security of chemical facilities. Modernizing policies and regulations—including the RMP Rule—falls under this umbrella.

A July 2014 Request for Information (RFI) sought initial comment on potential revisions to RMP under the EO. This was followed by a Small Business Advocacy Review (SBAR) Panel discussion in November 2015. On March 14, 2016, the USEPA published Proposed Rule: Accidental Release Prevention Requirements: Risk Management Programs Under the Clean Air Act, Section 112(r)(7), outlining proposed amendments to the RMP Rule.

Since the initial action to revise the RMP Rule commenced two and a half years ago, the USEPA has received over 60,000 public comments and has had extensive engagement with nearly 1,800 people.

Final Amendments

The much anticipated final RMP amendments were published in the Federal Register on January 13, 2017. According to the USEPA, these amendments are intended to:

- Prevent catastrophic accidents by improving accident prevention program requirements

- Enhance emergency preparedness to ensure coordination between facilities and local communities

- Improve information access to help the public understand the risks at RMP facilities

- Improve third-party audits at RMP facilities

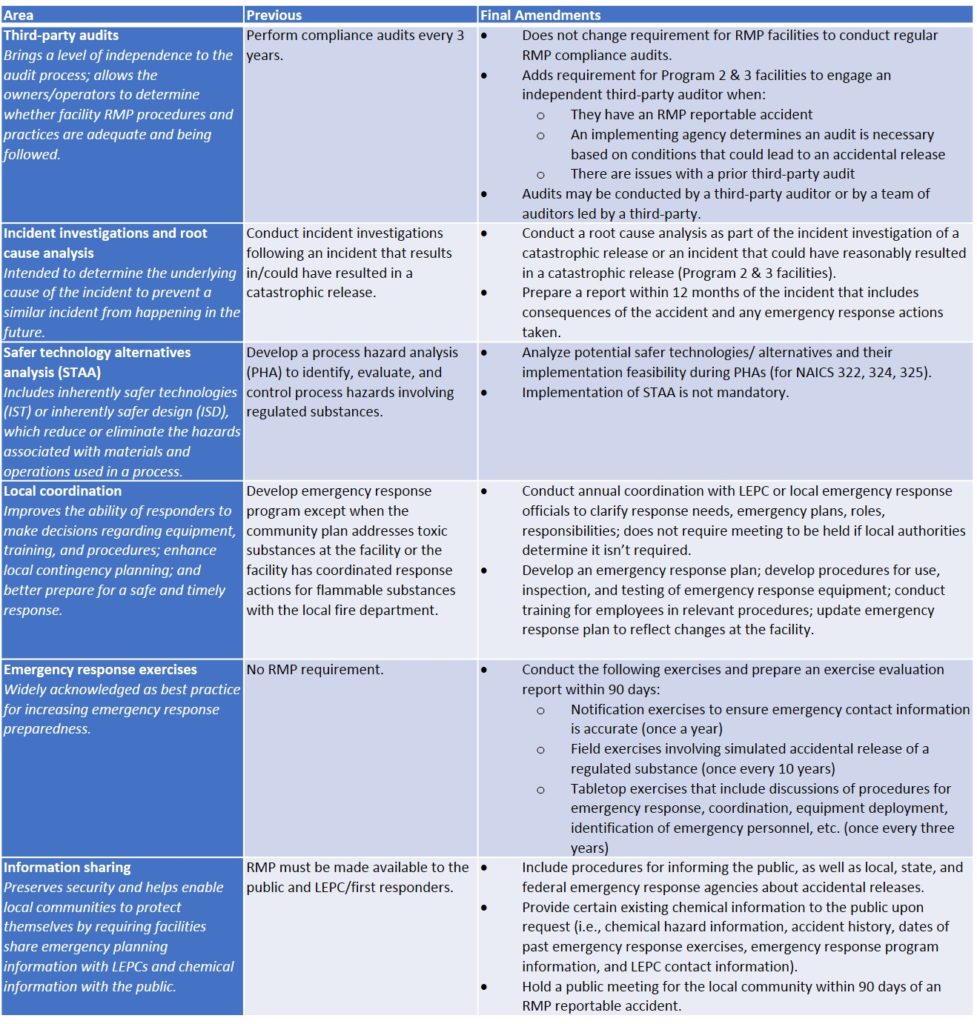

The final changes in the RMP Rule are outlined in the table below.

Compliance

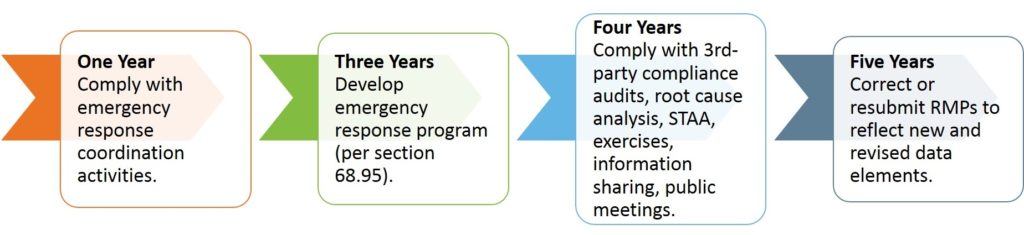

The effective date for the final RMP amendments is March 14, 2017. Compliance dates are set according to this date, as follows:

The effective date for the final RMP amendments is March 14, 2017. Compliance dates are set according to this date, as follows:

The Future of RMP

The final RMP amendments have the potential to significantly affect the 12,500 facilities in the U.S. that are subject to the RMP program. However, like many environmental rules, RMP faces an uncertain future under the Trump Administration. It is not clear at this point whether the final RMP Rule will actually be implemented as published—or at all.

Among the possible outcomes, environmental law firm Beveridge & Diamond PC cites the following possibilities:

- Congress may rescind the Rule using the Congressional Review Act.

- The USEPA might stay the Rule and then unilaterally seek to repeal it through amendment.

- The Rule might be challenged through a petition for reconsideration to the USEPA or a petition for review by the federal courts.

Kestrel will continue to track the RMP Rule and potential upcoming actions or compliance dates that may affect impacted facilities.

Case Study: Efficient Compliance Management

Regulatory enforcement, customer and supply chain audits, and internal risk management initiatives are all driving requirements for managing regulatory obligations. Many companies—especially those that are not large enough for a dedicated team of full-time EHS&S staff—struggle with how to effectively resource their regulatory compliance needs.

The following case study talks about how The C.I. Thornburg Co., Inc. (C.I. Thornburg) is using a technology tool to efficiently meet National Association of Chemical Distributors (NACD) and a number of other regulatory requirements.

The Challenge of Compliance

C.I. Thornburg joined NACD in January 2015. As a condition of membership, the company started the process of developing and implementing Responsible Distribution in April 2015. Responsible Distribution showcases member companies’ commitment to continuous improvement in every business process of chemical distribution—and it requires rigorous management activities to develop and maintain.

With an EHS&S department of one, managing all of those activities was a challenge for C.I. Thornburg. The company was looking for a way to streamline the process and more effectively manage Responsible Distribution requirements and regulatory compliance obligations.

Code & Compliance Elite™

C.I. Thornburg brought on Kestrel to initially help the company achieve Responsible Distribution verification. Kestrel worked with C.I. Thornburg to customize and implement Code & Compliance Elite (CCE™), an easy-to-use technology tool designed to effectively manage management system and verification requirements. Kestrel tailored the CCE™ application specifically for C.I. Thornburg to provide:

- Document management – storage, access, and version control

- Mobile device access

- Regulatory compliance management and compliance obligation calendaring

- Internal audit capabilities

- Corrective and preventive action (CAPA/CPAR) tracking and management

- Task and action management

CCE™ played a large role toward the end of C.I. Thornburg’s Responsible Distribution implementation, particularly with document control and organization, and in the verification audit. During verification, documents could be quickly referenced because of how they are organized in CCE™, making the process very efficient. According to C.I. Thornburg Director of Regulatory Compliance and EHS&S Richard Parks, “The verifier was blown away by how well we were organized and how the tool linked many documents from different regulatory policies.” The company achieved verification in May 2016.

Broadening to Other Regulatory Requirements

CCE™ is still being used to manage Responsible Distribution requirements, but C.I. Thornburg is now working with Kestrel to expand it to all regulatory branches that govern the business. Regulatory requirements function similarly—for example, Responsible Distribution has 13 codes, Department of Homeland Security (DHS) has 18 performance standards (RBPS), and OSHA PSM has 14 elements. All require internal audits and corrective action tracking—things that can be easily and effectively managed through CCE™ to create a one-stop shop for regulatory compliance. Kestrel is currently developing the DHS and PSM modules in CCE™ for C.I. Thornburg.

Valuable Management Tool

CCE™ is providing C.I. Thornburg with a valuable management tool that automates the regulatory landscape. According to Parks, as a small organization that depends on using efficient tools to manage compliance rather than adding more manpower, CCE™ has provided huge cost savings and tremendous value for the organization, including the following:

- CCE™ has become the ultimate tool inefficiency. Tasks that used to take hours to complete are now easily done in just minutes.

- The internal audit function of CCE™ makes audits seamless and tracking and follow-up easy.

- The CAPA tool ensures that the company is managing corrective actions and completing follow-up activities and tasks.

- The functionality of CCE™ allows for managing multiple regulatory dashboards, providing a one-stop shop for managing regulatory compliance obligations.

- CCE™ creates an organized document structure that enables easy access to information and quick response to auditors.

- During Senior Management Review, senior managers see the benefit of being able to reference the history of corrective actions and audits through CCE™.

“A lot of NACD member companies are small organizations that have limited resources to effectively manage all EHS&S needs,” said Parks. “CCE™ really creates the department and is a huge value to small businesses. With the CCE™ technology and a company’s clearly defined goal, Kestrel can provide an efficient solution to most any need.”

Comments: No Comments

Frank R. Lautenberg Chemical Safety Act

Last year, we came to you with breaking news about Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA) reform taking hold, as the U.S. House of Representatives passed the TSCA Modernization Act of 2015 (H.R. 2576) on June 23, 2015.

Almost one year later—and approximately 40 years since the Act’s inception—President Obama signed the Frank R. Lautenberg Chemical Safety Act (FRL-21) into law on June 22, 2016, amending the nation’s primary chemical management law. A historic bipartisan achievement, this Act gives the USEPA immediate authority to begin evaluating the risk of any chemical it designates as “high priority”.

Background

TSCA was developed to ensure that products are safe for intended use by providing the USEPA authority to review and regulate chemicals in commerce. Despite its intention, TSCA has proven to be rather ineffective in providing adequate protection and in facilitating U.S. chemical manufacturing and use. More than 80,000 chemicals available in the U.S. have never been fully tested for their toxic effects on health and the environment. In fact, under TSCA, the USEPA has only banned five chemicals since 1976.

According to a blog by USEPA Administrator Gina McCarthy, “While the intent of the original TSCA law was spot-on, it fell far short of giving EPA the authority we needed to get the job done.”

And that is where FRL-21 takes over, strengthening the foundation built by TSCA to ensure that chemical safety remains paramount.

Key Changes

FRL-21 remains consistent with the 2009 Principles for TSCA Reform. The USEPA outlines the following key regulatory changes in its Q&A briefing on the Act.

Evaluates the safety of existing chemicals in commerce, starting with those most likely to cause risks. This is the first time that all chemicals in commerce will undergo risk-based review by the USEPA. The Agency is charged with creating a risk-based process to determine which chemicals should be prioritized for assessment. High-priority chemicals may present an unreasonable risk to health or the environment due to potential hazard and route of exposure. A high-priority designation, in turn, triggers a risk evaluation to determine the chemical’s safety. This prioritization ensures that those chemicals that present the greatest risk will be reviewed first.

Evaluates new and existing chemicals against a new risk-based safety standard. Under the law, the USEPA will evaluate chemicals based purely on the health and environmental risks they pose. The evaluation must also include considerations for vulnerable populations (e.g., children, elderly, immune-compromised). FRL-21 further repeals the requirement that the Agency apply the least burdensome means of adequately protecting against unreasonable risk from chemicals. Costs and benefits will not be factored into the evaluation.

Empowers USEPA to require the development of chemical information necessary to support these evaluations. In short, the Agency has expanded authority to demand additional health and safety or testing information from manufacturers and/or to conduct risk evaluations on a chemical. USEPA may also expedite the process through new order and consent agreement authorities.

Enforces clear and enforceable deadlines that ensure timely review of prioritized chemicals and timely action on identified risks. Strict deadlines are designed to keep the USEPA’s work on track and to ensure compliance by manufacturers. For example, the Agency must have 10 ongoing risk evaluations within the first 180 days and 20 ongoing risk evaluations within 3.5 years. When unreasonable risks are identified, USEPA must then take final risk management action within two years. Action, which may include labeling, bans, and phase-outs, must begin no later than five years after the final regulation.

Increases public transparency of chemical information by limiting unwarranted claims of confidentiality. The USEPA must review and make determinations on all new confidentiality claims for chemical identity, as well as review past confidentiality claims to determine if they are still warranted. This will allow companies to preserve their intellectual property and competitive advantage, while still providing transparency to the public.

Provides a source of funding for the USEPA to carry out these changes. The USEPA can collect up to $25 million annually in user fees from chemical manufacturers and processors when they:

- Submit test data for USEPA review

- Submit a pre-manufacture notice for a new chemical

- Manufacture or process a chemical that is the subject of a risk evaluation

- Request that the USEPA conduct a chemical risk evaluation

Impacts

For companies, the most immediate impacts of FRL-21 will be on the new chemicals review process, as the USEPA has to approve any new chemical or significant new use of an existing chemical before manufacturing can commence and chemicals can enter the marketplace. This process will help provide regulatory certainty throughout the supply chain—from raw material produces to retailers. And, in the end, the risk evaluations will help ensure that manufacturers are able to bring new chemicals to the market in a safe and efficient way.

As for the general public, FRL-21 creates a new standard of safety to protect the public and the environment from unreasonable risks associated with chemical exposure. For the first time in 40 years, it provides assurance and greater confidence that chemicals are being used safely.

Environment / Quality / Safety

Comments: No Comments

Management System Internal Audit: What to Expect

Many companies face requirements to conduct management system internal audits. And many probably consider it to be one of those “necessary evils” of doing business. In reality, an internal audit can be a great opportunity to uncover issues and resolve them before an external audit begins. An internal audit can sometimes even enable more improvements than an external audit because it allows the company to review processes more often and more thoroughly. So what, exactly, goes into an internal audit?

What Is an Audit?

First, conducting a management system internal audit encompasses all of the efforts to gather, accumulate, arrange, and evaluate data so that there is sufficient information to arrive at an audit opinion. According to the ANSI/ASQC Standard Q1-1986 Generic Guidelines for Auditing Management Systems, an audit is:

a systematic examination of the acts and decisions by people with respect to Q/EHS issues, in order to independently verify or evaluate and report conformance to the operational requirements of the program or the specification or contract requirement of the product or service.

Internal audits should be carried out to look for areas for improvement and best practices. In an internal audit, the auditor is evaluating, verifying, and reporting conformance or non-conformance in terms of related documentation. The auditor assesses systems, processes, and products against the related documentation:

- Systems are compared against company directives and requirements.

- Processes are compared against procedures, process charts, and work instructions.

The auditor examines where and how “operational requirements of the management system” are described. This is done by reviewing each policy, procedure, work instruction, checklist, and form looking for each “actionable item” listed within.

The Interview

The auditor will go out into the workforce and ask the prepared questions to various employees. Based on the responses given, the auditor may need to ask follow-up questions to get a clear understanding of how an operation works. Questions asked by auditors are generally open-ended to give the auditee the opportunity to elaborate. The auditor’s goal is to give the employee the opportunity to think prior to answering and to follow the audit trail wherever it leads—within or outside of the department.

Tangible Evidence

In order for an internal audit to support improvement steps, the auditor will seek tangible evidence. For example, work instructions require that inspections are completed every day, but the checklist shows that no checks have been performed for the last week. Tangible evidence may include taking a photo copy of the checklist to document this issue.

Evaluating Internal Controls

During the audit, the auditor is looking for internal controls that regulate an operation. There are seven steps in evaluating internal controls:

- Observe the Operation: The auditor needs to understand what processes and systems to review, where they are located, and who is responsible for them.

- Identify Constraints: The auditor will identify constraints to the extent possible, such as:

- Scattered information

- Internal opposition

- Process not capable

- Process not in control

- Unavailable information

- Evaluate Risk: The auditor will assess the importance and risk of internal controls not detecting and preventing non-conformances. The auditor will ask personnel being audited and management if there is anything more that could be done to identify and control risk.

- Evaluate the Internal Control Structure: Usually extensive internal controls exist, operate properly, and maintain/improve the process; however, this may not be an accurate assumption. Controls may not exist, may be weak, or may control and measure unimportant variables. It is very important for the auditor to resist assuming that the way an existing system has been set up is the correct way to do something. Auditors should challenge how and why something is being done to encourage system improvements.

- Test the Effectiveness of the Internal Control Structure: Gathering evidence is the process of collecting data and information critical to support a decision or judgment rendered by the auditor.

- Evaluate Evidence: Once evidence has been gathered from interviews, observations, or records, the auditor must distill and summarize the data into useful information for the company. The evidence is then reviewed to determine whether systems and controls are working effectively.

- Issue an Opinion: When all is said and done, the auditor must issue an opinion of conformance or non-conformance. In a deficiency finding (non-conformance), the audit report will clearly state that there is a variance between what is and what should be. All evidence findings should be listed to support this conclusion.

Clarify Issues and Non-Conformances

Upon completion of an audit, there may be times when clarification of an issue or concern will be warranted. This is when the auditor may go back to the department head and review the current understanding of the audit results. The department head should have ample time to discuss and clarify any issues of concern.

Any outstanding issues that warrant a non-conformance report should be discussed to ensure that the company understands: 1.) why the issue is considered a non-conformance, and 2.) what may need to be done to rectify the situation. It is important to also discuss all positive findings from the audit to leverage best practices.

By using an internal audit to actually improve operations—and not just as another requirement to fulfill—companies can realize significant value through:

- Meeting regulatory/certification requirements prior to the external audit

- Improving operational controls and processes

- Enhancing overall management system effectiveness

Comments: 1 Comment

Hazardous Materials Management Plan (HMMP)

An ever-growing area of concern across the industry is the appropriate management of hazardous materials and waste. The number of government regulations concerning hazardous materials handling alone is significant—from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) and Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), to the Department of Transportation (DOT), Department of Homeland Security (DHS), Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA), and Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC). Under these laws, the disposal of hazardous material in the sewer system, stormwater system, on the ground, or in regular trash is regulated by a number of prohibitions.

In addition to these regulations, there are international codes for hazardous materials —developed by the International Fire Code (IFC)/International Building Code (IBC) and operationalized by local officials—that apply across the industry. Kestrel has found that more and more facilities, particularly those in retail warehousing, are being subjected to the requirements of these codes.

IFC/IBC Requirements

Local fire marshals have the responsibility to inspect facilities and ensure that hazardous materials are properly managed and stored. Although local requirements may vary, most local laws have closely adopted the IFC/IBC requirements for hazardous materials management.

The IFC/IBC requirements reference hazardous material as it relates to hazard classes—a significant difference compared to some of the other hazardous materials regulations across the U.S. Applicability and specific requirements are based on:

- Hazard class of the chemical

- Volume of the chemical

- How the chemical is used

- How the chemical is stored

- Building occupancy

Depending on these things, the local fire marshal may require the facility to develop a Hazardous Materials Management Plan (HMMP), conduct a Hazardous Materials Inventory, and/or submit a Hazardous Materials Permit.

HMMP Requirements

The purpose of a Hazardous Materials Management Plan (HMMP) is to describe the company’s procedures for storing, using, managing, and disposing of hazardous materials in a safe manner.

The information requested for an HMMP is different than that required for Tier II reporting under Section 312 of the Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act (EPCRA). The purpose of the Tier II form is to provide state and local officials and the public with information on the general hazard types and locations of hazardous chemicals at the facility.

Notable differences between Tier II and HMMP include the following:

- Classifications and regulations are different.

- Volumes that trigger an HMMP are much lower.

- Use and storage of the chemical, as well as the occupancy of the building, influence the requirements for an HMMP.

Beyond the HMMP, a company may need to conduct a Hazardous Materials Inventory, which requires defining hazard classes for chemicals at the facility and may need to apply for a Hazardous Material Permit under the authority of the local fire marshal.

While there may be variations by the local authority, in general, the Plan and Inventory include the following:

| Hazardous Materials Management Plan (HMMP) | Hazardous Materials Inventory |

|

|

Hazard Classes and MAQs

Hazard classes, as required in the Hazardous Materials Inventory, are listed in IFC Appendix E. They include physical hazards and health hazards, and typically have a number of associated subcategories. A hazard class is not listed on a Safety Data Sheet (SDS). The classes include:

- Explosives

- Compressed Gases

- Flammable and combustible liquids

- Flammable solids

- Combustible dust and powders

- Oxidizers

- Organic Peroxides

- Pyrophoric materials

- Unstable materials

- Water reactive materials

- Cryogenic materials

- Toxic materials

- Corrosives

The MAQ for a hazardous material will determine occupancy requirements and required controls (sprinkler systems, temperature controlled storage etc.). The MAQs are located in:

- IBC Table 307.1(1) and IFC Table 5003.1.1(1) for physical hazard hazardous materials

- IBC Table 307.1(2) and IFC Table 5003.1.1(2) for health hazard hazardous materials

- IFC Tables 5003.1.1(3) and (4) for outdoor control area MAQ

Note that the IBC and IFC are both involved to determine the hazard classification and the associated storage limits and requirements.

Moving Forward

Companies with hazardous materials must manage their hazardous materials safely. To ensure that they are meeting the IFC/IBC requirements, it is beneficial for companies to:

- Check with the local fire marshal to determine what needs to be done to meet local requirements, including engineering design requirements.

- Prepare and maintain a facility map identifying storage areas, sprinkler systems, emergency plans, etc. and document it in an HMMP.

- Contact vendors/installers of sprinkler systems and other equipment to ensure that the systems are designed for their intended use. The installer is a good resource for what would be allowed in a particular area and what the limitations of the system might be. This should be verified by qualified engineers.

- Conduct a Hazardous Materials Inventory, if required, to define hazard classes. This may require outside assistance to appropriately classify chemicals.

- Complete any special Hazardous Materials Permits, if required.

- Comply with the conditions of a Permit and with the technical specifications for activities such as maintenance; recognize and manage any changed conditions.

- Regularly inspect and audit the systems for compliance.

Managing hazardous materials is a part of doing business safely. Satisfying local fire marshal requirements will further help ensure that the company, the environment, and the surrounding community remain unharmed.

Comments: No Comments

Risk Management Plan (RMP) Changes: Proposed Rule

Since President Obama issued Executive Order (EO) 13650, Improving Chemical Facility Safety and Security, in August 2013, Kestrel has been following the USEPA’s efforts to carry out the EO, specifically as it relates to the Risk Management Plan (RMP) rule.

After extensive information gathering over the past two years, including issuing a Request for Information (RFI) and conducting Small Business Advocacy Review (SBAR) panels, the USEPA announced its proposed revisions to the RMP regulations on February 25, 2016.

Why RMP?

While chemicals are obviously an important part of so many aspects of our lives, improper handling and management can result in catastrophic releases that have severe and lasting impacts—loss of life, injury, property damage, community disruption.

The RMP Rule implements Section 112(r) of the Clean Air Act Amendments, and is aimed at preventing and/or reducing the severity of accidental chemical releases. RMP applies to all stationary sources with processes that contain more than a threshold quantity (TQ) of a regulated substance (based on toxicity, volatility, and flammability criteria). These sources must comply with the RMP regulations by taking defined steps to prevent accidents and by preparing and submitting an RMP to USEPA at least every five years.

Despite the RMP Rule, according to the February 25 USEPA press release referenced above, “While numerous chemical plants are operated safely, in the last 10 years more than 1,500 accidents were reported by RMP facilities. These accidents are responsible for causing nearly 60 deaths, some 17,000 people being injured or seeking medical treatment, almost 500,000 people being evacuated or sheltered-in-place, and costing more than $2 billion in property damages.”

These impacts—amongst other things—reinforce the EO and highlight the importance of modernizing the existing RMP Rule to:

- Improve chemical process safety

- Assist authorities in planning for and responding to accidents

- Improve public awareness of chemical hazards at regulated sources

Proposed Rule

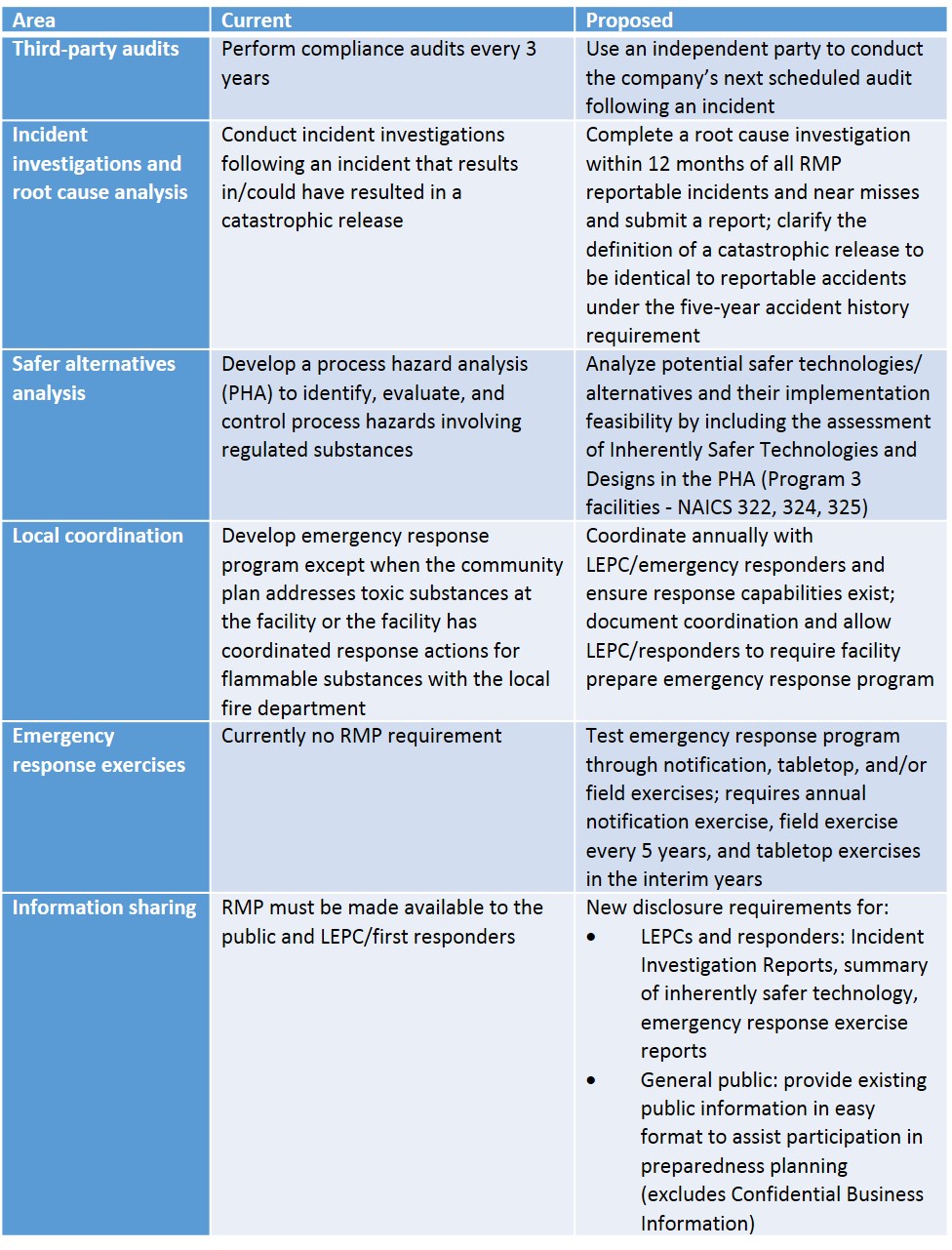

The proposed amendments, as outlined in the table below, are intended to improve the requirements to enhance chemical safety at RMP facilities. Of important note, the USEPA is not proposing any revisions to the list of regulated substances under RMP at this time; however, the Agency may propose additions to this list in a separate action.

Things to Consider

There are a number of alternatives that the USEPA is still considering the proposed changes outlined above. The Agency plans to hold a public meeting to allow stakeholders to comment on the proposed rule; written comments may also be submitted within 60 days after the proposed rule is published in the Federal Register.

In reviewing and commenting on the proposed rule, it is important to consider the following:

- How might the proposed amendments impact your business?

- What additional and/or different criteria for third-party auditors should be required?

- What clarification may be required to effectively coordinate with LEPCs?

- What information is appropriate to share to improve emergency coordination with local responders and the community?

- What issues does your facility foresee with rule compliance?

Again, the proposed changes to the RMP Rule represent just one of the actions that the U.S. government is undertaking to improve chemical safety and security. Kestrel will continue to track these amendments, as well as other actions and decisions that may impact chemical facility operations.

Tips to Prepare for an Internal Audit

All types of business and operational processes demand a variety of audits and inspections to evaluate compliance with standards—ranging from government regulations, to industry codes, to system standards (e.g., ISO), to internal corporate requirements. Audits offer a systematic, objective tool to assess compliance across the workplace and to identify any opportunities for improvement.

Routine internal audits are becoming a larger part of organizational learning and development. They provide a valuable way to communicate performance to decision makers and key stakeholders. Even more importantly, audits help companies identify areas of noncompliance and opportunities for improvement.

For some audits, a company may work with a third-party auditor. This can be valuable in getting an objective assessment of overall compliance status if executed effectively. Here are some best practice tips to help prepare for an internal audit—and ensure that it goes smoothly:

- Audit scope: Make sure that the scope of the audit is well defined and documented (i.e., regulations, management system standards, company policies). This also involves identifying which areas and functions onsite are included. For example, if contractors are leasing space, are their areas in scope or out? What about other onsite lessees, if any?

- Documents, plans, and records: Prior to the audit, ask the auditor for a list of documents they may be looking for (e.g., OSHA logs, past audit findings). Depending on the nature of the audit, it can be an extensive list and knowing ahead of time will save time and money. If possible, collect all records in advance and have them easily accessible. If corporate policy allows, it is often advisable to send current versions of all facility-specific plans, permits, and other documents to the auditor in advance of the audit to aid in preparation and create a more efficient use of time onsite. When the auditor arrives, make sure you know where relevant records are and that they are available to the auditor (i.e., not locked up in someone else’s office). Records should be organized by type in separate folders and sorted by date. Not only does that save time, it creates less likelihood of a record being overlooked. In most cases, electronic versions of records are sufficient, as long as they can be easily retrieved and viewed on the computer.

- Interviews: Advise individuals who may be interviewed during the audit about the purpose of the audit. Communicate well in advance of the audit so that employees aren’t caught off guard when they see an individual walking around taking notes and pictures. Prepare your employees; encourage them to cooperate and provide helpful information when asked. Every employee should:

- Be aware of the company quality/environmental/safety/food safety policy and able to state it in their own words.

- Be aware of the quality/environmental/safety/food safety objectives the company has set for the current time period (i.e., what the company is working on to improve the current “state”).

- Understand how they “make a difference” (i.e., how just by doing their jobs, they are following company policy and objectives and impacting performance).

- Be knowledgeable about the procedures and practices required for doing their job properly.

- Schedule: Ask for an audit schedule. This can help you plan for when certain “in-the-know” people need to be available. This can save valuable time—especially for those individuals—and help ensure that those you absolutely need for the audit are available when you need them.

- Be available: Questions often arise during an audit. It is helpful to assure that qualified and knowledgeable personnel are available to answer questions and clarify information during the audit, in addition to being present during the audit debriefing.

- Housekeeping: Good housekeeping puts auditors at ease. Conversely, lax housekeeping is often a harbinger of compliance issues and may put auditors on heightened alert.

- Care of a third-party auditor: Make sure there is adequate work space available for the auditor to review records and other documents—with power, a desk or table, good lighting, and access to internet/email to exchange documents during the audit.

- Confidentiality: If the audit scope involves regulatory compliance and the company has elected to employ audit privilege mechanisms, make sure that all parties are aware of the means to be taken to ensure that audit privilege is preserved (e.g., marking notes and documents, limiting distribution of output, adhering to state-specific requirements).

8 Functions of Compliance–Building a Reliable Foundation

Virtually every regulatory program—environmental, health & safety, security, food safety—has compliance requirements that call for companies to fulfill a number of common compliance activities. Addressing all (or those specified in the applicable regulation) of the eight compliance functions outlined below can be instrumental in establishing or improving a company’s capability to comply.

- Inventory means taking stock of what you have. For compliance purposes, the inventory is quite extensive, including (but not limited to) the following:

- Activities and operations (i.e., what you do – raw material handling, storage, production processes, fueling, maintenance, etc.)

- Human resources (i.e., who does what)

- Emissions

- Wastes

- Hazardous materials

- Discharges (operational and stormwater-related)

The outcome of a compliance inventory is an operational and EHS profile of the company’s operations and sites. In essence, the inventory is the top filter that determines the applicability of regulatory requirements and guides compliance plans, programs, and activities.

- Authorizations, permits & certifications provide a “license to construct, install, or operate.” Most companies are subject to authorizations/permits at the federal, state, and local levels. Common examples include air permits, operating permits, Title V permits, safe work permits, tank certifications, construction authorization. In addition, there may be required fire and building codes and operator certifications. Once the required authorizations, permits, and/or certifications are in place, some regulatory requirements lead companies to the preparation and updating of plans as associated steps.

- Plans are required by a number of regulations. These plans typically outline compliance tasks, responsibilities, reporting requirements, schedule, and best management practices to comply with the related permits. Common compliance-related plans may include SPCC, SWPPP, SWMP, contingency, food safety management, and security plans.

- Training follows once you have your permits and plans in place. It is crucial to train employees to follow the plans so they can effectively execute their responsibilities and protect themselves and the community. Training should cover operations, safety, security, and environment.

- Practices in place involve doing what is required to follow the terms of the permits and related plans. These are the day-to-day actions (regulatory, best management practices, planned procedures, SOPs, and work instructions) that are essential for following the required process.

- Monitoring & inspections provide compliance checks to ensure that the site is operating within the required limits/parameters and that the company is achieving operational effectiveness and performance expectations. This step may include some physical monitoring, sampling, and testing (e.g., emissions, wastewater). There are also certain regulatory compliance requirements for the frequency and types of inspections that must be conducted (e.g., forklift, tanks, secondary containment, outfalls). Beyond regulatory requirements, many companies have internal monitoring/inspection requirements for things like housekeeping and process efficiency.

- Records provide documentation of what has been done related to compliance—current inventories, plans, training, inspections, and monitoring required for a given compliance program. Each program typically has recordkeeping, records maintenance, and retention requirements specified by type. Having a good records management system is essential for maintaining the vast number of documents required by regulations, particularly since some, like OSHA, have retention cycles for as long as 30 years.

- Reports are a product of the above compliance functions. Reports from ongoing implementation of compliance activities often are required to be filed with the regulatory agency on a regular basis (e.g., monthly, quarterly, semi-annually, annually), depending on the regulation. Reports also may be required when there is an incident, emergency, or spill.

Reliable Compliance Performance

Documenting procedures on how to execute these eight functions, along with management oversight and continual review and improvement, are what eventually get integrated into an overarching management system (e.g., environmental, health & safety, food safety, security, quality). This documentation helps create process standardization and, subsequently, consistent and reliable compliance performance.

In addition, completing and organizing/documenting these eight functions of compliance provides the following benefits:

- Helps improve the company’s capability to comply on an ongoing basis

- Enhances confidence in compliance practices by others, providing an indication of commitment, capability, and reliability

- Creates a strong foundation to answer auditors’ questions (agencies, customers, certifying bodies, internal)

- Establishes compliance practices for when an incident occurs

- Helps companies know where to look for continuous improvement

- Reduces surprises and unnecessary spending on reactive compliance-related activities

- Informs management’s need to know