MichBio U: EHS Regulatory Overview for Labs

January 20, 2021 | 11 am – 12 pm ET

Cost: FREE for members, $19 for nonmembers

Join KTL Senior Consultant Liz Hillgren and MichBio for a high-level overview of the EHS regulations that might be applicable to laboratories. The webinar will discuss typical lab regulatory challenges and provide an overview of the major requirements for OSHA, EPA, and DOT compliance, including plans, reporting, training, and programs.

Comments: No Comments

SQF V9: Planning for Changes

The Safe Quality Food (SQF) Program is a rigorous food safety and quality program. Recognized by the Global Food Safety Initiative (GFSI), the SQF codes are designed to meet industry, customer, and regulatory requirements for all sectors of the food supply chain. SQF certification showcases certified sites’ commitment to a culture of food safety and operational excellence in food safety management.

In May 2021, SQF will be releasing Edition 9 (SQF V9) to align the code with the latest GFSI benchmarking criteria, updated regulatory requirements, and scientific changes. According to the SQF Institute, SQF V9 is designed to help certified sites meet and exceed all industry, customer, and regulatory requirements so they can remain competitive across sectors. V9 is scheduled for implementation with audits beginning May 24, 2021.

Significant Changes

The SQF V9 changes are broken down into two categories of changes:

Structural Changes

- Development of Custom Codes for certain industry-specific sectors (livestock, animal feed, petfood, aquaculture, dietary supplements)

- Streamlined technical elements to reduce redundancy in the following sections:

- Site location and operation

- Food safety culture

- Chemical storage

- Personal hygiene

- Specifications

- Training

Technical Changes

- GFSI benchmarking requirement updates, including changes to:

- Food safety culture requirements

- Internal laboratory requirements

- HACCP plan requirements for storage and distribution

- Remote activities requirements

- SQF stakeholder feedback updates, including changes to:

- Co-manufacturers’ requirements

- Ambient air testing requirement

- Audit scoring

New or updated concepts that present some of the greatest changes under SQF V9 include the following:

- Food Safety Culture Requirements: Senior leadership is required to lead and support a food safety culture within the site.

- Additional Training Requirements: Training requirements are now defined for sampling and test methods, environmental monitoring, allergen management, food defense, and food fraud for all relevant staff.

- Labeling Requirements: Updates to Product Identification Section now emphasize labeling requirements and checks during operations and require the implementation of procedures to ensure label use is reconciled.

- Substitute SQF Practitioner: All sites are now required to have a designated substitute SQF Practitioner with HACCP training and competencies in maintaining the food safety plan and knowledge of the SQF Food Safety Code.

Planning for Change

For companies that are SQF-certified, now is the ideal time to assess current SQF program elements, identify improvements that are internally desirable and required by the new standard, and implement those updates that will make the SQF program more useful to the business. This can be done through a series of phases to ensure adoption throughout the organization.

Phase 1: SQF Assessment

An assessment should begin by reviewing the following:

- Existing SQF programs, processes, and procedures

- Existing document management systems

- Employee training tools and programs

This documentation review and program assessment will help to identify elements of the existing SQF program that are acceptable, those that show opportunities for improvement, and those that may be missing, including those needed for development and implementation to meet the requirements of SQF V9.

Phase 2: SQF Program Updates

The assessment will inform a plan for updating the SQF certification program, including major activities, key milestones, and expected outcomes. Development/update activities included on the plan may include the following:

- Updating current SQF programs, processes, and procedures with missing V9 requirements

- Developing new SQF programs, processes, and procedures for additional V9 requirements

- Updating training programs with any new and additional requirements

- Revising document register to align with SQF V9 numbering changes

- Updating records and forms with any new and additional requirements

- Updating Food Safety Policy to include new food safety culture requirements

When implementing program updates, leveraging existing management system and certification program elements and utilizing proven approaches can greatly streamline the process.

Phase 3: Training

To ensure staff are prepared to implement and sustain the updated SQF V9 program, training is important. This includes training for affected staff on applicable requirements; specific plans, procedures, and GMPs developed to achieve compliance; and the certification roadmap to prepare for future audits.

Following this plan now will help companies ensure they maintain their SQF certification when audits begin under SQF V9 in May 2021–and that certification matters when it comes to meeting customer and regulatory requirements, protecting the company brand, and keeping consumers safe.

Comments: No Comments

KTL News: Expanding Resources

KTL is pleased to announce the addition of the following individuals to our team.

Jessica Dykun, Senior Consultant

Jessica is a Senior Consultant with more than a decade of experience working in the food and beverage industry, with particular expertise in food safety and quality assurance (FSQA). Jessica has lent her expertise on a variety of KTL food projects over the past several years; we are happy to welcome her as a KTL employee. Jessica is certified in HACCP and Lean Six Sigma and as an FSSC Lead Auditor. Read her full bio… jdykun@kestreltellevate.com | 724-544-8416

April Greene, Consultant

April is an experienced EHS professional with a demonstrated history of working in the environmental services industry. She brings a strong chemistry and laboratory background to her work at KTL. She is particularly skilled in sustainability, data analysis, and analytical chemistry and has significant experience managing quality, facilities, safety, and regulatory compliance in a laboratory setting. Read her full bio… agreene@kestreltellevate.com | 608-799-2166

Samantha Hunt, Consultant

Samantha has a diverse background in the food and beverage industry, with particular expertise in food safety and quality assurance. Prior to joining KTL, she served in a variety of quality and lab management roles, with a specialized focus on beverage companies and fermentation science. Through her previous positions, Samantha has developed in-depth knowledge of FDA food safety regulations as they apply in laboratory, manufacturing, and packaging settings. Read her full bio… shunt@kestreltellevate.com | 828-470-8258

Erica Schein, Consultant

Erica has a strong background working in the food safety and quality control environment. She excels at researching and conducting programs to manage food safety requirements and ensure overall safety. Through her previous positions, Erica has developed in-depth knowledge of FDA and USDA regulations as they apply to a leading wholesale distribution center. She has in-the-field experience managing the daily operations of a highly effective and compliant food safety program. Read her full bio… eschein@kestreltellevate.com | 773-456-5210

Comments: No Comments

How Episodic Generation Works

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has provided generators of hazardous waste some options for managing unanticipated waste events and large-scale cleanouts that have not be acceptable in the past. Under the Hazardous Waste Generator Improvement Rule, episodic generation allows small quantity generators (SQGs) and very small quantity generators (VSQGs) of hazardous waste to maintain their generator status, even if they have an occurrence of waste generation that would normally push them into a higher generator status.

It is a fairly straightforward concept, in theory, that allows VSQGs and SQGs the flexibility to have one planned (e.g., regular maintenance, tank cleanouts, short-term projects, removal of excess chemical inventory, or chemical cleanouts) or unplanned (e.g., production process upsets, product recalls, accidental spills, acts of nature) event per year that creates an increase in the generation of hazardous wastes that exceeds quantity limits for the generator’s usual status.

If—or when—an episodic generation event occurs, there are very specific requirements that must be followed. KTL has assisted many companies through this process with great success, resulting in minimized risk, less threat of negative inspection results, and overall cleaner facilities. The case study below walks through an actual unplanned event and how the facility responded to maintain compliance with its SQG status.

Case Study: Episodic Generation Event

An Iowa company has a printing process that generates contaminated (used) solvent when it cleans its press and changes ink colors. Because the company generates more than 220 pounds (100 kilograms) but less than 2,200 pounds (1,000 kilograms) of hazardous waste per month, it is considered an SQG.

The company uses new and recycled solvent to formulate their inks for printing and to clean the press between printing runs. A distillation unit onsite is used to process used solvent for re-use in the processes.

Processing Breakdowns

During the first week of August, the company experienced two processing breakdowns that resulted in the unplanned generation of large quantities of hazardous waste:

- A piece of production equipment malfunctioned and contaminated all the ink in the facility and the press with microscopic ceramic fragments.

- Within the same week, the distillation unit had a thermocouple malfunction, and the used solvent began to accumulate.

These dual challenges resulted in a large generation event of excess contaminated waste ink and used solvent. The facility surpassed the SQG hazardous waste threshold quantities. An event such as this falls under the category of an unplanned episodic generation event. The company determined it needed to conduct an episodic generation cleanup event and set a goal of disposing of all hazardous waste by the end of August.

Steps to Compliance

As a first step, the company notified the EPA by phone within 72 hours of the event. The company also completed the initial notification form required by EPA requesting a one-time episodic event that would increase their generator status to LQG for the month and submitted it. Then, they began the coordination for disposal with the disposal facility and the transporter.

The facility disposed of all contaminated ink and solvent generated the first week of August by August 27 (within the 60-day requirement). During this time, the presses were flushed, the distillation unit was repaired, the facility began production, and the solvent recycling process resumed.

After all waste was disposed from the property, the company completed the final notification form for the EPA and returned to SQG generation levels by September 1. All manifests, land disposal notifications, and documentation are retained in an episodic generation file onsite. Additionally, KTL assisted in the development of a comprehensive overview document that explained all aspects of the episodic event so any future inspections would be completed with little question or concern about the event.

Requirements

An event such as the one described in this case study is a prime example of an unplanned episodic generation event. Accordingly, the facility was required to respond. Among the most significant requirements the facility had to satisfy to maintain its SQG status include:

- Notifying the EPA within 72 hours after an unplanned event (or at least 30 days before a planned event) using EPA Form 8700-12.

- Obtaining an EPA ID number (if the generator does not already have one) BEFORE initiating the shipment of generated waste.

- Completing the event and shipping the episodic waste off site within 60 days of starting the event, whether planned or unplanned, using a hazardous waste manifest, hazardous waste transporter, and RCRA-designated facility.

- Completing and maintaining records onsite for three years after the completion date of the episodic event.

Additional Details

It is important to note some additional details about episodic generation that are important for VSQGs and SQGs to know and understand:

- Typically, a generator is only allowed to have one episodic event per year, whether planned or unplanned; however, the generator may petition the EPA or state for a second event, provided the second event is the opposite type (i.e., planned vs. unplanned). The petition must include:

- Reason for and nature of the event

- Estimated amount of hazardous waste being managed

- How the hazardous waste will be managed

- Estimated length of time needed to complete the management, not to exceed 60 days

- Information regarding the previous episodic event (e.g., nature of the event, planned or unplanned, how the generator complied)

- An episodic event cannot last more than 60 days beginning on the first day episodic hazardous waste is generated and concluding on the day the hazardous waste is removed from the generator’s site. If the hazardous waste is not off site within 60 days, then it must be counted toward the generator’s monthly generation levels.

- The following are NOT considered episodic events and would impact overall generator status:

- Increased waste related to increased production

- An accident or spill due to operator error, abuse, or lack of maintenance (i.e., irresponsible management of hazardous waste/materials)

- Any activity that is part of the normal course of business

- Discovering at the end of the month that the monthly generation thresholds have been exceeded

- Short-term generation differs from episodic generation. A short-term generator is an entity that does not normally generate hazardous waste but has a one-time, non-recurring, temporary event (typically less than 90 days) unrelated to normal operational activities. Short-term generators are not relieved of any regulatory requirements tied to the volume of hazardous waste generated and must meet all generator requirements for the level of generator (i.e., notification, manifesting, reporting, contingency planning, and training).

The episodic waste provision allows SQGs and VSQGs to avoid the increased burden of a higher generator status when generating episodic waste—provided it is properly managed. In the past, this wasn’t an option, unless states provided special exception. Now it is part of EPA’s objective to provide greater flexibility in how hazardous waste is managed through the Hazardous Waste Generator Improvements Rule. If your company is interested in exploring a plant-wide chemical cleanup or experiences a production challenge that results in the generation of hazardous waste at a rate that is higher than your generator status allows, KTL can provide the expertise necessary to guide you through the episodic generation process.

Comments: No Comments

Understanding Hazardous Terminology

When it comes to regulatory compliance, “hazardous” is an important term. Unfortunately, what is considered “hazardous” can be very confusing with the varying hazardous terms and definitions used across multiple regulatory agencies.

Overlapping Terminology

The fact is that different regulations have different definitions for similar terms, and these regulations are applied for different purposes. The same material can take on multiple descriptors—or not—depending on which regulations apply:

- Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) uses the term hazardous waste to protect human health and the environment (40 CFR 261 and 268).

- Department of Transportation (DOT) uses the term hazardous materials to ensure materials are managed safely in all modes of transport—air, road, marine, and rail (49 CFR 172).

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) uses the term hazardous substances and focuses on worker safety (29 CFR).

Sometimes, this terminology overlaps; sometimes it doesn’t. That is why it is critical to understand the differences between hazardous terms and to use each term appropriately—so you know what requirements apply.

EPA: Hazardous Waste

According to EPA, a hazardous waste is “a contaminated chemical or byproduct of a production process that no longer serves its purpose and needs to be disposed of in accordance with the EPA.”

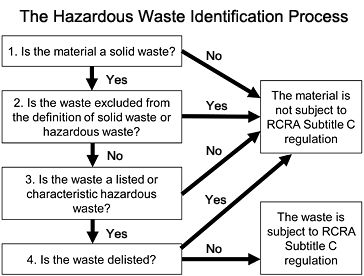

Hazardous waste is generated from many sources, ranging from industrial manufacturing process wastes to batteries, and may come in many forms (e.g., liquids, solids, gases, and sludges). To determine whether a waste is considered “hazardous,” EPA has developed a flowchart identification process (pictured below).

EPA’s Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) establishes the regulatory framework for managing hazardous waste. The degree of regulation that applies to each hazardous waste generator depends on the amount of hazardous waste produced.

Unless it is managed at the facility, hazardous waste generated must eventually be transported off site for disposal, treatment, or recycling. At this point, DOT regulations kick in for the transportation of freight, including the transport of RCRA hazardous waste.

DOT: Hazardous Material

DOT has the authority to regulate the transportation of hazardous materials under the Hazardous Materials Transportation Act (HMTA), which is overseen by the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA) division of DOT. A DOT hazardous material is defined as “a substance (gas, liquid, or solid) capable of creating harm to people, environment, and property.”

By definition, hazardous materials are capable of posing an unreasonable risk to health, safety, and property in commerce. This includes substances, wastes, marine pollutants, elevated temperature materials, and items included in DOT’s Hazardous Materials Table (HMT – 49 CFR 172.101) (e.g., laboratory chemicals, solvents, alcohol, acids, compressed gases, cleaners, pesticides, paints, infectious substances, radioactive materials). Note that anything excluded from the EPA’s Hazardous Waste Manifest requirements is not considered a hazardous waste by DOT when shipped but may be considered a hazardous material. This is a tricky nuance but very important for shippers to understand. Correspondingly, DOT has rigorous training requirements.

Hazardous materials are legally defined by class, characteristic, and name:

- Class 1: Explosives

- Class 2: Gases

- Class 3: Flammable Liquid

- Class 4: Flammable Solids

- Class 5: Oxidizing Substances, Organic Peroxides

- Class 6: Poisonous (Toxic) and Infectious Substances

- Class 7: Radioactive Materials

- Class 8: Corrosives

- Class 9: Miscellaneous Dangerous Goods

OSHA: Hazardous Substance

Finally, OSHA defines a hazardous substance as “any substance or chemical that is a ‘health hazard’ or ‘physical hazard,’ including:

- Chemicals that are carcinogens, toxic agents, irritants, corrosives, sensitizers;

- Agents that damage the lungs, skin, eyes, or mucous membranes;

- Chemicals that are combustible, explosive, flammable, oxidizers, pyrophorics, unstable-reactive or water-reactive; and

- Chemicals which, in the course of normal handling, use, or storage, may produce or release dusts, gases, fumes, vapors, mists or smoke that may have any of the previously mentioned characteristics.”

Chemical hazards and toxic substances are addressed in several specific OSHA standards for general industry (29 CFR 1910 Subpart Z). OSHA’s Hazard Communication Standard (HCS – 29 CFR 1910.1200) is designed to ensure that information about chemical and toxic substance hazards in the workplace and associated protective measures is disseminated to workers and that the workers understand how to apply this knowledge to complete their job tasks safely.

Under HCS, manufacturers must provide a safety data sheet (SDS) for all hazardous substances they produce or import. The SDS conveys physical and health impacts, as well as procedures for exposures, spills, leaks, and disposal to employees and any downstream customers. Materials in transport must be properly labeled according to the HCS (i.e., flammable, explosive, radioactive), as well as meet DOT requirements.

In an additional OSHA program–Hazardous Waste Operations and Emergency Response (HAZWOPER)—all employees must be trained on emergency response, spill management, and risk minimization. This training covers:

- Code requirements

- Hazard classes, risk identification, hazardous communication

- Site safety programs

- Proper selection use of appropriate PPE and respiratory protection

- Advanced spill management and emergency response procedures

- Risk minimization, emergency management, and engineering controls

The Overlap: An Example

Let’s see how these definitions come together in practice.

A DOT-regulated hazardous material that expires and becomes unusable might be regulated as a hazardous waste under EPA’s RCRA program. For example, if a company uses acetonitrile in their operations, when the company receives the acetonitrile as a product, it is transported to the company as a DOT Class 3 Flammable Liquid using a Bill of Lading as the shipping papers. If that same acetonitrile passes its expiration date and is unusable by the company, it must be shipped as a DOT Class 3 Flammable Liquid.

Additionally, the generator (the company) must determine which waste codes are applicable. In this example, expired acetonitrile would have the waste code D001, indicating it is a flammable waste. Because this was also an unused commercial chemical product, the expired acetone would have a waste code of U009 to comply with EPA hazardous waste regulations. Small and Large Quantity Generators (SQGs/LQGs) of hazardous waste would also have to ship the hazardous waste using a Hazardous Waste Manifest as the shipping paper versus a Bill of Lading.

A hazardous material or waste released to the environment in a quantity above a certain threshold, referred to as a Reportable Quantity, might be regulated as a hazardous substance for EPCRA reporting purposes. For example, if a tanker truck is delivering acetonitrile to the same facility, the acetonitrile is a hazardous material and meets the definition of a Class 3 Flammable Liquid. The Reportable Quantity for acetonitrile is 5,000 lbs. according to 49 CFR 172.102, Table 1. If the tanker truck is in an accident and 5,000 lbs. of acetonitrile spills (or is released to the environment), the trucking company must report the spill to the National Response Center to comply with EPA EPCRA regulations.

Importance of Training

As this example shows, there is much overlap between the different hazardous terminology and regulations—and getting it all correct is not always simple. This explains why rigorous training is required to meet compliance requirements for managing hazardous waste. OSHA, EPA, and DOT each have requirements for personnel who are working with chemicals, hazardous waste, or onsite emergency management activities:

- OSHA 1910.1200 (HazComm) requires all employees to be trained in label reading and SDS review for chemicals they may encounter in the workplace.

- OSHA 1910.120 (HAZWOPER) requires any employees who are in positions that may respond to chemical spills or emergencies onsite to be trained in chemical risk recognition, spill control basics, emergency response, and additional requirements depending on the level of response expected.

- DOT code (49 CFR 172.702) requires that any employee involved in the transportation (shipping or receiving) of hazardous materials must be trained and tested in general awareness, site-specific job functions, and transportation security.

- EPA code (40 CFR 266 and 273) requires that any employee taking part in chemical waste management (hazardous or universal) must be trained in proper waste disposal practices.

Making sure the right people get the right training will help ensure the organization understands hazardous terminology and correctly interprets the requirements related to hazardous substances the facility manufactures, uses, stores, or transports.

Comments: No Comments

Regulatory Alert: SQG Re-notification Requirement

EPA’s Hazardous Waste Generator Improvements Rule became effective on May 30, 2017. This Rule is designed to make the RCRA hazardous waste generator regulations easier to understand; provide greater flexibility in how hazardous waste is managed; and improve environmental protection. The final rule includes over 60 revisions and new provisions to the hazardous waste generator program.

One of these notable provisions, which impacts small quantity generators (SQG), is the requirement for SQGs to re-notify EPA or their state agency about their hazardous waste activities every four years. The first re-notification is due by September 2021. Since this is the first time EPA is requiring this of SQGs, many are not as aware of this specific re-notification requirement—and it is one that will impact many.

Who’s an SQG?

Let’s take a step back and first define who is considered an SQG. According to EPA, SQGs are those facilities that generate more than 100 kilograms but less than 1,000 kilograms of hazardous waste per month. EPA cites the following major requirements for SQGs:

- SQGs may accumulate hazardous waste onsite for 180 days without a permit (or 270 days if shipping a distance greater than 200 miles).

- The quantity of hazardous waste onsite must never exceed 6,000 kilograms.

- SQG are limited to one episodic event per calendar year (40 CFR 262.230).

- SQGs must comply with the following requirements:

- Hazardous waste manifest (40 CFR 262, subpart B)

- Pre-transport (40 CFR 262.30-33)

- Preparedness and prevention (40 CFR 262.16(b)(8) and (9))

- Land disposal restriction (40 CFR 268)

- Management of hazardous waste in tanks or containers (40 CFR 262.16(b)(2) and (3))

- There must always be at least one employee available to respond to an emergency. SQGs are not required to have detailed, written contingency plans.

And, starting in 2021, SQGs are required to re-notify EPA or their state environmental agency regarding their generator status at least every four years.

Re-notification Requirement

The intent of the re-notification requirement is to create a more accurate and complete count of the federal SQG universe, helping EPA and authorized states conduct oversight, enforcement, and planning. Ultimately, the data collected will allow EPA to identify those SQGs that are active and to remove those that are inactive from the database.

To meet the re-notification requirement, SQGs must complete and submit the Notification of RCRA Subtitle C Activities (i.e., Site Identification Form – also known as EPA Form 8700-12) or the state equivalent in full. The requirement for generators to re-notify whenever there is a change to the site contact, ownership, or type of RCRA Subtitle C hazardous waste activity conducted remains in place. Note: An SQG that submits a complete re-notification within the four years before an SQG renotification deadline would be considered in compliance with this provision.

Facilities can elect to fill out the paper form or may submit electronically via MyRCRAID, an electronic reporting system for submitting to the EPA Site Identification Form. Some states have their own forms that are equivalent to the Site Identification Form, also meeting the requirement of the regulation. In states where there is a more frequent re-notification or reporting requirement, the SQG should comply with its state deadline.

Ensuring Compliance

As generators consider this re-notification requirement and the other Hazardous Waste Generator Rule provisions, it is important to:

- Get a solid understanding of the rule for the state(s) in which the generator operates. Requirements, forms, frequency, etc. may vary from state to state and compared to EPA.

- Ensure the inventory of types and quantities of hazardous waste generated at the facility is current and documented.

- Review the Site Identification Form and determine what additional data needs to be gathered in advance of the September 2021 submittal deadline.

Comments: No Comments

Staff Spotlight on Liz Hillgren

Get to know our KTL team! This month, we are catching up with Senior Consultant Liz Hillgren. Liz brings over 20 years of environmental experience in both industry and consulting to the KTL team. She is based in Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Tell us a little bit about your background—what are your areas of expertise?

My background is in hazardous waste. I worked for transfer, storage, and disposal facilities (TSDFs) for 20 years. I have worked at a landfill, a stabilization facility, a fuel blender, a used oil recycler, and a wastewater treatment facility. I have managed technical groups but also customer service throughout my career in industry.

What types of clients do you work with? What are the biggest issues you see them facing right now?

My KTL customers are largely manufacturing facilities. Most of them are mid-sized, so they don’t always have tons of money—but they do have real regulatory issues.

What would you say is a highlight of your job?

I like to help my customers solve problems, because I feel like I am part of their team. I also like to learn new things—my job always has something new to think about.

What do you like to do in your free time?

I am a gardener, and I enjoy being outside. I live in an old house full of projects and potential. I like to sew. I just started beekeeping, so that is currently where all my time and money are spent!

Read Liz’s full bio.

Comments: 1 Comment

FDA’s New Era of Smarter Food Safety

The food system is rapidly evolving—from new foods, to new formulations, to new production and delivery methods. As a whole, the industry is pushing into untapped areas, facing supply chain challenges, and responding to unique market demands, including those that have quickly emerged as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., e-commerce, new delivery models, virtual inspections).

To keep pace with all this change, the Food & Drug Administration (FDA) announced the New Era of Smarter Food Safety in April 2019. On July 13, 2020 (delayed from Spring 2020 due to COVID-19-related issues), the Administration subsequently published the New Era of Smarter Food Safety Blueprint. This blueprint outlines the approach FDA will take create a New Era of Smarter Food Safety that evolves along with food technologies and systems—and the impacts these changes will have on the food industry and consumers alike.

New Era: What to Expect

According to FDA, “The New Era of Smarter Food Safety represents a new approach to food safety, leveraging technology and other tools to create a safer and more digital, traceable food system.” That being said, the Administration further notes that “smarter food safety is about more than just technology. It’s also about simpler, more effective, and modern approaches and processes. It’s about leadership, creativity, and culture.”

Correspondingly, the New Era is built on four core elements to support FDA’s ultimate goal of reducing foodborne illness:

- Tech-Enabled Traceability

- Smarter Tools and Approaches for Prevention and Outbreak Response

- New Business Models and Retail Modernization

- Food Safety Culture

Importantly, the New Era does not replace or negate the progress of the Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA). Rather it builds on FSMA’s science and risk-based protections and uses them as the foundation for integrating more data, better analytics, and technological advancements going forward. FSMA’s full implementation remains a priority for the FDA. In FDA’s words, the New Era is “people-led, FSMA-based, and technology-enabled”.

Building the Blueprint

The New Era of Smarter Food Safety Blueprint is the roadmap FDA will follow to build its New Era and further food safety modernization under the FSMA rules. The blueprint includes goals to:

- Enhance traceability

- Improve predictive analytics

- Respond more rapidly to outbreaks

- Address new business models

- Reduce contamination of food

- Foster the development of stronger food safety cultures

Each of these goals is addressed by the core elements and the following actions, as outlined in the blueprint, which will be implemented over the next decade:

Core Element 1: Tech-enabled Traceability. Food traceability is the ability to track any food through all stages of the supply chain—production, processing, distribution—to ensure food safety and operational efficiency. The objective of Tech-enabled Traceability is to use technology to create traceability advancements, including implementing rapid tracebacks, identifying specific sources, and helping to quickly remove products from the marketplace when necessary. Beyond technology, part of this effort involves harmonizing efforts to follow food from farm to table by creating similar data standards across government and industry. As public health agencies increasingly rely on electronic data in outbreak investigations, quality and compatibility must be addressed to more quickly and accurately trace the origin of contaminated food. Blueprint actions include:

- Developing foundational components

- Encouraging and incentivizing industry adoption of new technologies

- Leveraging the digital transformation

Core Element 2: Smarter Tools and Approaches for Prevention and Outbreak Response. One of the most powerful resources available to create this New Era is data. However, that power lies in collecting better quality data, conducting more meaningful analysis, and transforming data into more strategic, prevention-oriented actions. The blueprint seeks to strengthen procedures and protocols for conducting root cause analyses to identify how a food became contaminated and then for using predictive analytics to prevent future outbreaks. As under FSMA, the focus is on the preventive nature of modern food safety approaches. Blueprint actions include:

- Invigorating root cause analysis

- Strengthening predictive analytics capabilities

- Developing domestic mutual reliance

- Developing inspection, training, and compliance tools

- Improving outbreak response

- Implementing recall modernization

Core Element 3: New Business Models and Retail Food Modernization. How food is getting from farm to table is continually evolving. The recent pandemic is a prime example, as it has brought huge growth in distribution channels, including e-commerce and food delivery, carryout, and pickup. The FDA and industry must be prepared for new business models that continue to emerge with marketplace demands and consumer needs. The address this, blueprint actions include:

- Ensuring safety of food produced or delivered using new business models

- Modernizing traditional retail food safety approaches

Core Element 4: Food Safety Culture. According to the Safe Food Alliance, “Food safety culture refers to the specific culture of a facility: the attitudes, beliefs, practices, and values that determine what is happening when no one is watching. A strong culture of food safety helps a facility both to prevent and catch deviations in their processes that impact the safety, quality, and legality of their products.” Improvements in food safety, foodborne illness, and outbreaks depend largely on food safety culture, even more than technology. A strong food safety culture has always been a prerequisite to effective food safety management and that will continue in the New Era. Blueprint actions include:

- Promoting food safety culture throughout the food system

- Further promoting food safety culture throughout the Agency

- Developing and promoting a Smarter Food Safety consumer education campaign

Incorporating into Operations

As FDA has recognized, there is a real need for more “real-time, data-driven, nimble approaches to help ensure a strong and resilient food system”. The New Era of Smarter Food Safety Blueprint is FDA’s way to get there. It will be up to players in the food industry to take the core elements of the blueprint and begin to incorporate them into operations. As FDA rolls out this initiative, organizations should consider doing the following:

- Implement an information management system to help coordinate, organize, control, analyze, and visualize the information necessary to remain in compliance and operate efficiently.

- Conduct third-party assessments to provide an outside perspective of food safety systems and compliance/certification.

- Explore technological advancements that allow for further digitization and promote more timely and accurate collection and management of important data.

- Conduct root cause analysis, as needed, to identify underlying issues and ensure similar problems do not occur in the future.

- Build a strong food safety culture that focuses on changing from a reactionary to a preventive mindset that promotes safety and quality.

EHS Experts Roundtable

We recently sat down with three of KTL’s environmental, health, and safety (EHS) experts, Becky Wehrman-Andersen, Liz Hillgren, and Jake Taylor, to talk about all things EHS. The three Senior Consultants shared what they are seeing in the marketplace, as well as some of their best advice and lessons learned for managing EHS compliance.

What are some of the biggest EHS issues you see your clients facing right now?

Collectively, there are a few trends we see time and again, which generally can be tied back to many EHS “departments” (which often consist of just one person) lacking the resources—financial and personnel—to manage the sheer number of EHS requirements they are required to comply with.

We find that EHS personnel are being asked to manage a lot—and often in areas that may be outside their education/expertise/experience. So while they may have knowledge, in part, of EHS regulations, they often don’t have a comprehensive enough knowledge to always even know what they are missing. Add to this the fact that there is almost “too much” information available, and it can very quickly become overwhelming to determine what is applicable and what needs to be done to comply.

We see this creating several common scenarios:

- Entire compliance programs are being missed because customers do not realize they are subject to some requirements. In some cases, companies just don’t know what they don’t know.

- Frequently, companies may not understand the thought process of what needs to be in place to satisfy a standard’s requirements. For example, they may have OSHA training programs in place to meet requirements; however, they do not have the accompanying site-specific written programs and/or documentation that are also required for compliance.

- Often customers do not take the time or have the knowledge to identify the riskiest chemicals or processes onsite, which leads to elevated challenges in keeping employees and the surrounding environment safe.

How have you seen COVID impacting industry/your clients?

The majority of our clients have really adapted and responded to COVID as best they can. Many have remained busy and are doing just fine. However, the pandemic has resulted in operational challenges—from expanding shifts to separate people more, to having more “virtual workers,” to managing internal safety cost increases, to developing plans to juggle outbreaks. In some cases, this has slowed some policy/program development and impacted company culture. In addition, we are seeing a few companies experiencing supply chain challenges but to a lesser extent than anticipated. Understandably, there is also an element of frustration as guidance remains in flux, as well as concern as facilities “button up” for winter due to the elevated risks associated with closed spaces with little air circulation.

At the same time, companies are learning how to work with fewer people and conduct some business activities virtually. And many have been pushed into using technology that may have been available in the past but was never a necessity of doing business. Even though there have been some “bumps” in the road, people are catching on. In fact, KTL has been conducting audits, assessments, and training virtually, and our clients are seeing the benefits of a virtual approach on many levels. We anticipate some of this will continue as the new norm due to the business efficiencies it presents.

Are there any recent regulatory developments (or any on the horizon) that industry should be preparing for?

EPA has a provision as part of the 2016 Hazardous Waste Generator Improvements Rule that will be affecting small quantity generators (SQG) in 2021. The Agency is now requiring SQGs to renotify EPA or their state agency about their hazardous waste activities every four years. The first renotification is due by September 2021. Since this is the first time EPA is requiring this of SQGs, many are not as aware of the Hazardous Waste Generator Improvements regulations and this specific renotification requirement. It is one that will impact many. Read more from EPA.

Other regulatory changes on the forefront will likely depend largely on the outcomes of the election this November, and it is just too soon to predict.

Based on your experience, what are some best practices you would recommend to help companies ensure ongoing EHS compliance and meet business objectives?

- Conduct a comprehensive gap assessment to ensure you are meeting the requirements of all applicable EHS regulations. This should be the starting place for understanding your regulatory obligations and current compliance status.

- Organize your records. Know what records you need. Document your inspections and your training. Develop standard operating procedures (SOPs) so people know what to do.

- Seek third-party oversight. Having external experts periodically look inside your company provides an objective view of what is really going on, helps you to prepare for audits, and allows you to implement corrective/preventive actions that ensure compliance.

- Perform a comprehensive onsite risk assessment with associated risk minimization planning and plan/conduct annual spill drills to practice emergency response for hazardous chemical incidents.

- Create an integrated management system (e.g., ISO 9001/14001/45001, Responsible Distribution) by finding commonalities between the standards and leveraging pieces of each to develop a reliable system that works for your organization.

- Develop a relationship with someone you trust to do things in your best interest, understanding that EHS should be a process of continuous improvement. Use them to help you understand what regulations apply. Let them help you prioritize your compliance plan. Use them to do your annual training. Rely on them as a part of your team.

- Get senior leadership commitment. It is often clear how an organization prioritizes EHS with little digging. Even with the best EHS personnel, the organization and its EHS system will only be as good as the top leadership and what is important to them.

Do you have any good “lessons learned” to share about what to do when it comes to EHS compliance?

Just start! It is better to do some than none. Get organized. Determine what you need, break it down, set a schedule, use your consultant to keep you on target, and just get started. Something is definitely better than nothing.

KTL has coached several companies from a “zero to compliance” status and has also actively assisted in OSHA and EPA penalty negotiations. One company went from an anticipated $300,000 – $500,000 in penalty to ZERO penalty, reduced their generator status from large quantity generator (LQG) to very small quantity generator (VSQG), and achieved a more than 70% reduction in waste management costs simply through process changes and risk reduction strategies.

How important is technology when it comes to EHS compliance?

EHS personnel are starting to see the possibilities of how incorporating technology solutions can help them become more efficient in their operations and compliance processes. As stated above, COVID has pushed some technology innovations to the forefront as a means for companies to continue operating in different ways.

For example, technology tools can be very helpful with tracking requirements and documents—but it also requires good organization and communication. Custom apps for conducting inspections and regular checklists can be a simple way to create operational efficiencies, particularly for smaller organizations who may lack the initial financial resources to undertake an entire system implementation. Once that initial investment is made, companies often see the value of technology and the potential to implement a centralized compliance information management system to help manage and track compliance obligations, activities, and performance/status.

With technology, it is no longer a question of IF, it is just a matter of WHEN companies decide to jump on board. Technology and “Big Data” can—and should—be a focus of any EHS compliance program. The investment will pay off in the end.

What value do you see KTL providing?

We serve as an extension of a company’s EHS staff—from completing small tasks that never seem to get done to identifying large gaps in compliance and building systems to resolve those non-compliance issues. We are there to support, answer questions, provide technical knowledge, and help our customers achieve compliance. We are teachers, trainers, a sounding board, and an EHS support system. We have a great team of experts who know EHS, understand industry, and excel at creating solutions and tools to meet our clients’ needs. Trust is critical and we strive to be trustworthy. That is who KTL is.

Comments: No Comments

Maintaining Food Safety Compliance: Third-Party Assessments

Regulatory, customer, and industry standards require that Food Safety Management Systems (FSMS) and programs must be current at all times. They also require that any changes be verified and validated. Third-party assessments provide a means of confirming compliance specific to key programs, particularly when many certification audits are being postponed or limited in scope due to COVID concerns.

Focused Activity, Desired Results

As a focused activity, third-party assessments support food safety compliance and certification and respond directly to a company’s needs:

- Third-party assessments provide more direct coverage to evaluate specific program effectiveness and allow for a more focused understanding of existing strengths and improvement areas.

- Enlisting a qualified outside firm further provides an unbiased assessment, offers an opportunity to work with local resources, and allows for a more flexible timeframe.

- The assessment typically results in a report developed by a qualified source focused on closing corrective actions.

- It minimizes the overall disruption in business compared to a full certification-level audit.

Major Program Assessments

While third-party assessments are not uncommon in the food industry, they are generally not interwoven with industry certification audits. That being said, an FSMS is comprised of major programs or sections that are prime subjects for third-party assessment, including the following.

A Hazard Analysis and Risk-Based Preventive Controls (HARPC) third-party assessment is based on a customized workplan, as well as the updated HARPC/Preventive Controls for Human or Animal Food rule. Aligning the assessment with internal audit programs supports verification by providing direct recommendations for corrections and improvements. This approach provides the following benefits:

- Assessment can be completed and delivered more directly with the Food Safety Team.

- Recommendations from findings can be more directly implemented and issues can be closed.

- Results can be verified and validated internally, providing a record of corrections to be implemented, meeting regulatory requirements, and demonstrating alignment with the internal audit program.

- The assessment provides a means to confirm timing of program updates and to determine the next scheduled assessment.

Current Good Manufacturing Practices (cGMP) compliance extends to FDA Section 117 requirements, which must be maintained under FSMA as part of the Food Safety Plan. A gap assessment of existing cGMPs confirms programs are complete and current, provides verification of updates, and validates programs are documented. Independent verification can be scheduled on a more flexible timeframe using qualified resources based on preference. Focused assessments of cGMPs provide a fresh look at programs, improvement recommendations, and direct corrective actions that are in line with the company’s internal audit processes.

Building and equipment assessments support site commissioning requirements for food and handling. Typically, building elements are not a major focus; however, assessing building and equipment is imperative, as it provides for opportunities to correct risks not always identified by the audit:

- Drills down to maintenance practices and provides a clear focus on preventive maintenance.

- Provides a perspective on physical plant processes that allows for planned improvements and hygienic design implementations.

- Ensures the integrity of physical food plant and site asset conditions.

Supplier program assessment provides a stronger level review of the organization’s suppliers. This assessment provides an opportunity to update supplier criteria and ratings and bring a pragmatic perspective for change based on qualified vs. underperforming suppliers. A clear benefit of the assessment is the ability to highlight established supplier performance in a more detailed way than is typically included in an audit to generate possible improvements.

Training should be an established food program and cGMP from the initial implementation of an FSMS. In the past, training was looked at as more casual than formal. As requirements have progressed, training has become more challenging. A focused assessment determines effectiveness and consistency of training by:

- Drilling down to job level

- Identifying alternatives to make training more effective

- Incorporating a broader level of industry observations

- Providing for planned training processes and program improvements

- Addressing culture and language barriers

Recently, KTL Principal Bill Bremer and Thomas Paraboschi, DNV GL’s Supply Chain and Digital Assurance Services Manager, joined International Food Safety & Quality Network (IFSQN) for a Food Safety Friday Webinar to discuss the benefits of increasing safety and quality through non-certification assessments. Join the replay of their conversation and learn more about this topic.