Assessing Risk Management Program Maturity

Maturity assessments are designed to tell an organization where it stands in a defined area and, correspondingly, what it needs to do in the future to improve its systems and processes to meet the organization’s needs and expectations. Maturity assessments expose the strengths and weaknesses within an organization (or a program), and provide a roadmap for ongoing improvements.

Holistic Assessments

A thorough program maturity assessment involves building on a standard gap analysis to conduct a holistic evaluation of the existing program, including data review, interviews with key staff, and functional/field observations and validation.

Based on Kestrel’s experience, evaluating program maturity is best done by measuring the program’s structure and design, as well as the program’s implementation consistency across the organization. For the most part, a program’s design remains relatively unchanging, unless internal modifications are made to the system. Because of this static nature, a “snapshot” provides a reasonable assessment of the design maturity. While the design helps to inform operational effectiveness, the implementation/operational maturity model assesses how completely and consistently the program is functioning throughout the organization (i.e., how the program is designed to work vs. how it is working in practice).

Design Maturity

A design maturity model helps to evaluate strategies and policies, practices and procedures, organization and people, information for decision making, and systems and data according to the following levels of maturity:

- Level 1: Initial (crisis management) – Lack of alignment within the organization; undefined policies, goals, and objectives; poorly defined roles; lack of effective training; erratic program or project performance; lack of standardization in tools.

- Level 2: Repeatable (reactive management) – Limited alignment within the organization; lagging policies and plans; seldom known business impacts of actions; inconsistent company operations across functions; culture not focused on process; ineffective risk management; few useful program or project management and controls tools.

- Level 3: Defined (project management) – Moderate alignment across the organization; consistent plans and policies; formal change management system; somewhat defined and documented processes; moderate role clarity; proactive management for individual projects; standardized status reporting; data integrity may still be questionable.

- Level 4: Managed (program management) – Alignment across organization; consistent plans and policies; goals and objectives are known at all levels; process-oriented culture; formal processes with adequate documentation; strategies and forecasts inform processes; well-understood roles; metrics and controls applied to most processes; audits used for process improvements; good data integrity; programs, processes, and performance reviewed regularly.

- Level 5: Optimized (managing excellence) – Alignment from top to bottom of organization; business forecasts and plans guide activity; company culture is evident across the organization; risk management is structured and proactive; process-centered structure; focus on continuous improvement, training, coaching, mentoring; audits for continual improvement; emphasis on “best-in-class” methods.

A gap analysis can help compare the actual program components against best practice standards, as defined by the organization. At this point, assessment questions and criteria should be specifically tuned to assess the degree to which:

- Hazards and risks are identified, sized, and assessed

- Existing controls are adequate and effective

- Plans are in place to address risks not adequately covered by existing controls

- Plans and controls are resourced and implemented

- Controls are documented and operationalized across applicable functions and work units

- Personnel know and understand the controls and expectations and are engaged in their design and improvement

- Controls are being monitored with appropriate metrics and compliance assurance

- Deficiencies are being addressed by corrective/preventive action

- Processes, controls, and performance are being reviewed by management for continual improvement

- Changed conditions are continually recognized and new risks identified and addressed

Implementation/Operational Maturity

The logical next step in the maturity assessment involves shifting focus from the program’s design to a maturity model that measures how well the program is operationalized, as well as the consistency of implementation across the entire organization. This is a measurement of how effectively the design (program static component) has enabled the desired, consistent practice (program dynamic component) within and across the company.

Under this model, the stage of maturity (i.e., initial, implementation in process, fully functional) is assessed in the following areas:

- Adequacy and effectiveness: demonstration of established processes and procedures with clarity of roles and responsibilities for managing key functions, addressing significant risks, and achieving performance requirements across operations

- Consistency: demonstration that established processes and procedures are fully applied and used across all applicable parts of the organization to achieve performance requirements

- Sustainability: demonstration of an established and ongoing method of review of performance indicators, processes, procedures, and practices in-place for the purpose of identifying and implementing measures to achieve continuing improvement of performance

This approach relies heavily on operational validation and seeking objective evidence of implementation maturity by performing functional and field observations and interviews across a representative sample of operations, including contractors.

Cultural Component

Performance within an organization is the combined result of culture, operational systems/controls, and human performance. Culture involves leadership, shared beliefs, expectations, attitudes, and policy about the desired behavior within a specific company. To some degree, culture alone can drive performance. However, without operational systems and controls, the effects of culture are limited and ultimately will not be sustained. Similarly, operational systems/controls (e.g., management processes, systems, and procedures) can improve performance, but these effects also are limited without the reinforcement of a strong culture. A robust culture with employee engagement, an effective management system, and appropriate and consistent human performance are equally critical.

A culture assessment incorporates an assessment of culture and program implementation status by performing interviews and surveys up, down, and across a representative sample of the company’s operations. Observations of company operations (field/facility/functional) should be done to verify and validate.

A culture assessment should evaluate key attributes of successful programs, including:

- Leadership

- Vision & Values

- Goals, Policies & Initiatives

- Organization & Structure

- Employee Engagement, Behaviors & Communications

- Resource Allocation & Performance Management

- Systems, Standards & Processes

- Metrics & Reporting

- Continually Learning Organization

- Audits & Assurance

Assessment and Evaluation

Data from document review, interviews, surveys, and field observations are then aggregated, analyzed, and evaluated. Identifying program gaps and issues enables a comparison of what must be improved or developed/added to what already exists. This information is often organized into the following categories:

- Policy and strategy refinements

- Process and procedure improvements

- Organizational and resource requirements

- Information for decision making

- Systems and data requirements

- Culture enhancement and development

From this information, it becomes possible to identify recommendations for program improvements. These recommendations should be integrated into a strategic action plan that outlines the long-term program vision, proposed activities, project sequencing, and milestones. The highest priority actions should be identified and planned to establish a foundation for continual improvement, and allow for a more proactive means of managing risks and program performance.

Comments: No Comments

Federal Court Overturns RMP Delay

The EPA’s Risk Management Plan (RMP) Rule (Section 112(r) of the Clean Air Act Amendments) has garnered a lot of attention as its status as a rule has fluctuated since the RMP Amendments were published under the Obama Administration on January 13, 2017.

The latest development in the RMP saga came on August 17, 2018, when the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit ruled that EPA does not have authority to delay final rules for the purpose of reconsideration.

Background

The original RMP Amendments of 2017 were developed in response to Executive Order (EO) 1365, Improving Chemical Safety and Security, and intended to:

- Prevent catastrophic accidents by improving accident prevention program requirements

- Enhance emergency preparedness to ensure coordination between facilities and local communities

- Improve information access to help the public understand the risks at RMP facilities

- Improve third-party audits at RMP facilities

However, after EPA published the final rule, many industry groups and several states filed challenges and petitions, arguing that the rule was overly burdensome, created potential security risks, and did not properly coordinate with OSHA’s Process Safety Management (PSM) standard.

Under the Trump administration, EPA delayed the effective date of the rule by 20 months—until February 2019—and announced its plan to reconsider the rule’s provisions. On May 30, 2018, the RMP Reconsideration Proposed Rule was published and proposed to:

- Maintain consistency of RMP accident prevention requirements with the OSHA PSM standard

- Address security concerns

- Reduce unnecessary regulations and regulatory costs

- Revise compliance dates to provide necessary time for program changes

Recent Court Actions

In the most recent actions, the federal court ruled that the EPA can no longer delay enforcement of the RMP Rule. In its court opinion, the judges cited that the delay “makes a mockery of the statute” because it violates the CAA requirement to “have an effective date, as determined by the Administrator, assuring compliance as expeditiously as practicable.” The court further stated that the delay of the rule was “calculated to enable non-compliance.”

EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt countered that the EPA needed more time to weigh concerns, particularly those about security risks associated with chemical facilities disclosing information to the public.

The judges have noted that EPA can still substantively revise the RMP Rule and its compliance deadline(s); however, they reinforced that in the CAA, “Congress is seeking meaningful, prompt action by EPA to promote accident prevention.”

What’s Next?

The RMP Rule will not take effect immediately; EPA has time to appeal the decision and petition for rehearing. The earliest that the RMP Amendments (as originally published) could realistically go into effect is October 2018. Based on this, effective dates for requirements contained in the RMP Amendments would be as follows:

- Effective immediately: 3-year compliance audits in each covered process at the facility (original date: March 14, 2017)

- Effective immediately: Duty to coordinate emergency response activities with local emergency responders (original date: March 14, 2018)

- March 14, 2020: Emergency Response Program revisions

- March 15, 2021: Third-party auditor requirements; incident investigation and root cause analyses; safer technology and alternatives analyses/IST provisions; emergency response exercise; public availability of information

- March 14, 2022: Revised elements of RMP provisions in Subpart G

If a rehearing is granted, the timeline would likely extend further into the future. Meanwhile, comments are due on the RMP Reconsideration Proposed Rule on Thursday, August 23, 2018. Kestrel will continue to monitor developments with the RMP Rule, as its final status remains a moving target.

Audit Program Best Practices: Part 2

Audits provide an essential tool for improving and verifying compliance performance. As discussed in Part 1, there are a number of audit program elements and best practices that can help ensure a comprehensive audit program. Here are 12 more tips to put to use:

- Action item closure. Address repeat findings. Identify patterns and seek root cause analysis and sustainable corrections.

- Training. Training should be done throughout the entire organization, across all levels:

- Auditors are trained on both technical matters and program procedures.

- Management is trained on the overall program design, purpose, business impacts of findings, responsibilities, corrections, and improvements.

- Line operations are trained on compliance procedures and company policy/systems.

- Communications. Communications with management should be done routinely to discuss status, needs, performance, program improvements, and business impacts. Communications should be done in business language—with business impacts defined in terms of risks, costs, savings, avoided costs/capital expenditures, benefits. Those accountable for performance need to be provided information as close to “real time” as possible, and the Board of Directors should be informed routinely.

- Leadership philosophy. Senior management should exhibit top-down expectations for program excellence. EHSMS quality excellence goes hand-in-hand with operational and service quality excellence. Learning and continual improvement should be emphasized.

- Roles & responsibilities. Clear roles, responsibilities, and accountabilities need to be established. This includes top management understanding and embracing their roles/responsibilities. Owners of findings/fixes also must be clearly identified.

- Funding for corrective actions. Funding should be allocated to projects based on significance of risk exposure (i.e., systemic/preventive actions receive high priority). The process should incentivize proactive planning and expeditious resolution of significant problem areas and penalize recurrence or back-sliding on performance and lack of timely fixes.

- Performance measurement system. Audit goals and objectives should be nested with the company business goals, key performance objectives, and values. A balanced scorecard can display leading and lagging indicators. Metrics should be quantitative, indicative (not all-inclusive), and tied to their ability to influence. Performance measurements should be communicated and widely understood. Information from auditing (e.g., findings, patterns, trends, comparisons) and the status of corrective actions often are reported on compliance dashboards for management review.

- Degree of business integration. There should be a strong link between programs, procedures, and methods used in a quality management program—EHS activities should operate in patterns similar to core operations rather than as ancillary add-on duties. In addition, EHS should be involved in business planning and MOC. An EHSMS should be well-developed and designed for full business integration, and the audit program should feed critical information into the EHSMS.

- Accountability. Accountability and compensation must be clearly linked at a meaningful level. Use various award/recognition programs to offer incentives to line operations personnel for excellent EHS performance. Make disincentives and disciplinary consequences clear to discourage non-compliant activities.

- Deployment plan & schedule. Best practice combines the use of pilot facility audits, baseline audits (to design programs), tiered audits, and a continuous improvement model. Facility profiles are developed for all top priority facilities, including operational and EHS characteristics and regulatory and other requirements.

- Relation of audit program to EHSMS design & improvement objectives. The audit program should be fully interrelated with the EHSMS and feed critical information on systemic needs into the EHSMS design and review process. It addresses the “Evaluation of Compliance” element under EHSMS international standards (e.g., ISO 14001 and OHSAS 18001). Audit baseline helps identify common causes, systemic issues, and needed programs. The EHSMS addresses root causes and defines/improves preventive systems and helps integrate EHS with core operations. Audits further evaluate and confirm performance of EHSMS and guide continuous improvement.

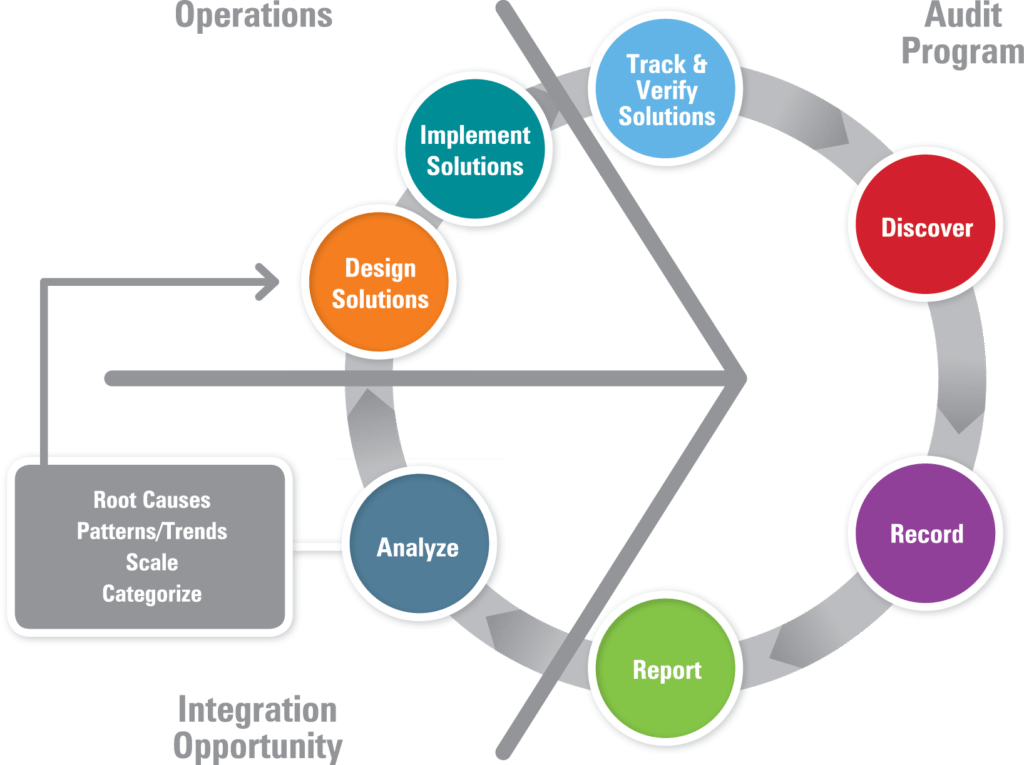

- Relation to best practices. Inventory best practices and share/transfer them as part of audit program results. Use best-in-class facilities as models and “problem sites” for improvement planning and training. The figure below illustrates an audit program that goes beyond the traditional “find it, fix it, find it, fix it” repetitive cycle to one that yields real understanding of root causes and patterns. In this model, if the issues can be categorized and are of wide scale, the design of solutions can lead to company-wide corrective and preventive measures. This same method can be used to capture and transfer best practices across the organization. They are sustained through the continual review and improvement cycle of an EHSMS and are verified by future audits.

Read the part 1 audit program best practices.

Audit Program Best Practices: Part 1

Audits provide an essential tool for improving and verifying compliance performance. Audits may be used to capture regulatory compliance status, management system conformance, adequacy of internal controls, potential risks, and best practices. An audit is typically part of a broader compliance assurance program and can cover some or all of the company’s legal obligations, policies, programs, and objectives.

Companies come in a variety of sizes with a range of different needs, so auditing standards remain fairly flexible. There are, however, a number of audit program elements and best practices that can help ensure a comprehensive audit program:

- Goals. Establishing goals enables recognition of broader issues and can lead to long-term preventive programs. This process allows the organization to get at the causes and focus on important systemic issues. It pushes and guides toward continuous improvement. Goal-setting further addresses the responsibilities and obligations of the Board of Directors for audit and oversight and elicits support from stakeholders.

- Scope. The scope of the audit should be limited initially (e.g., compliance and risk) to what is manageable and to what can be done very well, thereby producing performance improvement and a wider understanding and acceptance of objectives. As the program is developed and matures (e.g., Management Systems, company policy, operational integration), it can be expanded and, eventually, shift over time toward systems in place, prevention, efficiency, and best practices.

- Committed resources. Sufficient resources must be provided for staffing and training and then applied, as needed, to encourage a robust auditing program. Resources also should be applied to EHSMS design and continuous improvement. It is important to track the costs/benefits to compare the impacts and results of program improvements.

- Operational focus. All facilities need to be covered at the appropriate level, with emphasis based on potential EHS and business risks. The operational units/practices with the greatest risk should receive the greatest attention (e.g., the 80/20 Rule). Vendors/contractors and related operations that pose risks must be included as part of the program. For smaller, less complex and/or lower risk facilities, lower intensity focus can be justified. For example, relying more heavily on self-assessment and reporting of compliance and less on independent audits may provide better return on investment of assessment resources.

- Audit team. A significant portion of the audit program should be conducted by knowledgeable auditors (independent insiders, third parties, or a combination thereof) with clear independence from the operations being audited and from the direct chain of command. For organizational learning and to leverage compliance standards across facilities, it is good practice to vary at least one audit team member for each audit. Companies often enlist personnel from different facilities and with different expertise to audit other facilities. Periodic third-party audits further bring outside perspective and reduce tendencies toward “home-blindness”.

- Audit frequency. There are several levels of audit frequency, depending on the type of audit:

- Frequent: Operational (e.g., inspections, housekeeping, maintenance) – done as part of routine EHSMS day-to-day operational responsibilities

- Periodic: Compliance, systems, actions/projects – conducted annually/semi-annually

- As needed: For issue follow-up

- Infrequent: Comprehensive, independent – conducted every three to four years

- Differentiation methods. Differentiating identifies and distinguishes issues of greatest importance in terms of risk reduction and business performance improvement. The process for differentiating should be as clear and simple as possible; a system of priority rating and ranking is widely understood and agreed. The rating system can address severity levels, as well as probability levels, in addition to complexity/difficulty and length of time required for corrective actions.

- Legal protection. Attorney privilege for audit processes and reports is advisable where risk/liability are deemed significant, especially for third-party independent audits. To the extent possible, make the audit process and reports become management tools that guide continuous improvement. Organizations should follow due diligence elements of the USEPA audit policy.

- Procedures. Describe and document the audit process for consistent, efficient, effective, and reliable application. The best way to do this is to involve both auditors and those being audited in the procedure design. Audit procedures should be tailored to the specific facility/operation being audited. Documented procedures should be used to train both auditors and those accountable for operations being audited. Procedures can be launched using a pilot facility approach to allow for initial testing and fine-tuning. Keep procedures current and continually improve them based on practical application. Audits include document and record review (corporate and facility), interviews, and observations.

- Protocols & tools. Develop specific and targeted protocols that are tailored to operational characteristics and based on applicable regulations and requirements for the facility. Use “widely accepted or standard practice” as go-by tools to aid in developing protocols (e.g., ASTM site assessment standards; ISO 14010 audit guidance; audit protocols based on EPA, OSHA, MSHA, Canadian regulatory requirements; GEMI self-assessment tools; proprietary audit protocol/tools). As protocols are updated, the ability to evaluate continuous improvement trends must be maintained (i.e., trend analysis).

- Information management & analysis. Procedures should be well-defined, clear, and consistent to enable the organization to analyze trends, identify systemic causes, and pinpoint recurring problem areas. Analysis should prompt communication of issues and differentiation among findings based on significance. Audit reports should be issued in a predictable and timely manner. It is desirable to orient the audit program toward organizational learning and continual improvement, rather than a “gotcha” philosophy. “Open book” approaches help learning by letting facility managers know in advance what the audit protocols are and how the audits will be conducted.

- Verification & corrective action. Corrective actions require corporate review, top management-level attention and management accountability for timely completion. A robust root cause analysis helps to ensure not just correction/containment of the existing issue, but also preventive action to assure controls are in place to prevent the event from recurring. For example, if a drum is labeled incorrectly, the corrective action is to relabel that drum. A robust plan should also look for other drums than might be labeled incorrectly and to add and communicate an effective preventive action (e.g., training or posting signs showing a correctly labeled drum).

Read the part 2 audit program best practices.

10 Reasons to Implement a Management System

A management system is the framework that enables companies to achieve their operational and business objectives through a process of continuous improvement. In its simplest form, a management system implements the Plan, Do, Check, Act/Adjust cycle. Several choices are available for management systems (ISO is commonly applied), whether they are certified by third-party registrars and auditors, self-certified, or used as internal guidance and for potential certification readiness.

Business Benefits of a Well-Documented Management System

The connection between management systems and compliance is vital in avoiding recurring compliance issues and in reducing variation in compliance performance. In fact, reliable and effective regulatory compliance is commonly an outcome of consistent and reliable implementation of a management system.

Beyond that, there are a number of business reasons for implementing a well-documented management system (environmental, safety, quality, food safety, other) and associated support methods and tools:

- Establishes a common documented framework to achieve more consistent implementation of compliance policies and processes—addressing the eight core functions of compliance:

- Inventories

- Permits and authorizations

- Plans

- Training

- Practices in place

- Monitoring and inspection

- Records

- Reporting

- Provides clear methods and processes to identify and prioritize risks, set and monitor goals, communicate those risks to employees and management, and allocate the resources to mitigate them.

- Shifts from a command-and-control, centrally driven function to one that depends heavily on teamwork and implementation of a common system, taking into consideration the necessary local differences and building better know-how at the facility level.

- Establishes a common language for periodic calls and meetings among managers, facility managers, and executives, which yields better goal-setting, priority ranking, and allocation of resources to the areas with greatest risk or the greatest opportunity to add business value.

- Empowers facilities to take responsibility for processes and compliance performance without waiting to be told “what” and “how”.

- Enables better collaboration and communication across a distributed company with many locations.

- Enables the selection and implementation of a robust information system capable of tracking and reporting on common activities and performance metrics across the company.

- Employs a design and implementation process that builds company know-how, captures/retains institutional knowledge, and enables ongoing improvement without having to continually reinvent the wheel.

- Creates consistent processes and procedures that support personnel changes (e.g., transfers, promotions, retirements) and training of new personnel without causing disruption or gaps.

- Allows for more consistent oversight and governance, yielding higher predictability and reliability.

Environment / Quality / Safety

Comments: No Comments

Six Best Practices for Compliance Assurance

A well-designed and well-executed compliance assurance program provides an essential tool for improving and verifying business performance and limiting compliance risks. Ultimately, however, a compliance program’s effectiveness comes down to whether it is merely a “paper program” or whether it is being integrated into the organization and used in practice daily.

The following can show evidence of a living, breathing program:

- Comprehensiveness of the program

- Dedicated staff and resources

- Employee knowledge and engagement

- Management commitment and employee perception

- Internal operational inspections, “walk-abouts” by management

- Independent insider, plus third-party audits

- Program tailoring to greatest risks

- Consistency and timeliness of exception (noncompliance/nonconformance) disclosures

- Tracking of timely and adequate corrective/preventive action completion

- Progress and performance monitoring

Best Practices

To achieve a compliance assurance program on par with world-class organizations, there are a number of best practices that companies should employ:

- Know the requirements. This means maintaining an inventory of regulatory compliance requirements for each compliance program, as well as of state/local/contractual binding agreements applying to operations. It is vital that the organization keep abreast of current/upcoming requirements (federal, state, local).

- Plan and develop the processes to comply. Identify and assess compliance risks, and then set objectives and targets for performance improvement based on top priorities. From here, it becomes possible to then define program improvement initiatives, assign and document responsibilities for compliance (who must do what and when), develop procedures and tools, and then allocate resources to get it done.

- Assure compliance in operations. The organization needs to establish routine checks and inspections within departments to evaluate conformance with sub-process procedures. Process audits should be designed and implemented to cut across operations and sub-processes in order to evaluate conformance with company policies and procedures. Regulatory compliance audits should further be conducted to address program requirements (e.g., environmental, safety, mine safety, security). Audit performance must be measured and reported, and then expectations set for operating managers to take responsibility for compliance.

- Take action on issues and problems. Capture, log, and categorize noncompliance issues, process non-conformances, and near misses. Implement a corrective/preventive action process based on importance of issues. Be disciplined in timely completion, close-out, and documentation of all corrective/preventive actions.

- Employ management of change (MOC) process. Robust MOC processes help ensure that changes affecting compliance (to facility, operations, personnel, infrastructure, materials, etc.) are reviewed for their impacts on compliance. Compliance should be assured before the changes are made. Failure to do so is one of the most common root causes of noncompliance.

- Ensure management involvement and leadership. Set the tone at the top. The Board of Directors and senior executives must set policy, culture, values, expectations, and goals. It is just as important that these individuals are the ones to communicate across the organization, to demonstrate their commitment and leadership, to define an appropriate incentive/disincentive system, and to provide ongoing organizational feedback.

Comments: No Comments

Predictive Analytics in Incident Prevention

Companies are generating ever increasing amounts of data associated with business operations, leading to renewed interest in predictive analytics, a field that analyzes large data sets to identify patterns, predict outcomes, and guide decision-making. Companies are also facing a complex and ever expanding array of operational risks to proactively identify and mitigate. While many companies have begun using predictive analytics to identify marketing/sales opportunities, similar strategies are less common in risk management, including safety.

Classification algorithms, one general class of predictive analytics, could be particularly beneficial to the refining and petrochemical industries by predicting the time frame and location of safety incidents based on safety related inspection and maintenance data, essentially leading indicators. There are two main challenges associated with this method: (1) ensuring that leading indicators being measured are actually predictive of incidents, and (2) measuring the leading indicators frequently enough to have predictive value.

Kestrel’s article in the Q3 2018 edition of Petroleum Technology Quarterly (PTQ) features a case study to illustrate this process. Using regularly updated inspection data, the author developed a model to predict where broken rails are likely to occur in the railroad industry. The model was created using a logistic regression modified by Firth’s penalized likelihood method, and predicts broken rail probabilities for each mile of track. Probabilities are updated as additional data are collected.

In addition to predicted broken rail probabilities, the model identifies the variables with the most predictive validity (those that significantly contribute to broken rails). Using the model results, the railroad was able to identify exactly where to focus maintenance, inspection, and capital improvement resources and what factors to address during these activities. Validation tests of the model revealed 70% of the actual broken rail incidents occurred on the 20% of segments at highest risk for broken rails.

The same methodology could be used in the refining and petrochemical industries to manage risks by predicting and preventing incidents, provided that organizations:

- Identify leading indicators with predictive validity

- Regularly measure leading indicators (inspection, maintenance, and equipment data)

- Create a predictive model based on measured indicators

- Update the model as data are gathered

- Use the outputs to prioritize maintenance, inspections, and capital improvement projects and review operational processes/practices.

Integrating Technology into Traditional Processes

Traditional processes tend to produce traditional results. You can’t expect technological innovation without technological integration. The key is identifying the traditional processes that yield benefits (most likely cost or time savings) from technological integration. Doing this allows companies to stretch and empower every limited resource.

Fix It & Find It

Take the business practice of internal auditing as an example. The most traditional practice for internal auditing (e.g., environmental, safety, DOT compliance, ISO 9001, food safety) is a “find it & fix it” cycle, where the internal auditor goes out into a facility and audits operations as they exist. During the audit, the auditor identifies issues based on a standard set of protocols. The auditor typically walks a facility with a notepad and pencil taking notes of field observations that aren’t in compliance. Following the audit, the auditor creates a report and shares the findings with a responsible party. This can take weeks or even months. The cycle is repeated when the auditor comes back at a later time to check the site again.

The “find & fix” audit cycle works, but only to a point. The difficult part comes next. What happens with that inspection form or accident investigation report after it is completed? It is likely reviewed by a few people, perhaps transcribed into electronic form by a data entry clerk, and filed away someplace for legal and compliance reasons, rarely (if ever) to be seen again.

Filing data away in a drawer is better than nothing because it does show some documentation of findings, but that is where the benefits end. What happens when the auditor is asked to compile year-long data from the findings? How do you evaluate patterns and trends to best allocate your limited resources for improvement initiatives? The paper method of recordkeeping makes compiling field data into a report an enormous task.

Electronic Data Capture

If the auditor were to capture all the field data via smart phone or tablet at the point of discovery, the task of generating a report to analyze trends would be much easier. When data is collected, uploaded, and stored in a database, accessing and reporting on the data becomes as easy as asking a question. Questions like, “How many deficient issues were there at the warehouse last year?” or “How many overdue action items does Bruce have in repackaging?” can be answered by simply making a request of your data.

Data entered in the field can be used in many ways. Some applications written for devices allow you to print reports immediately from the smart phone and tablet device. Others require the data to first be uploaded to a desktop computer. Either way, the reports generated can include photos at the point of discovery and reference information, along with field comments. These reports support the auditor’s findings and remove questions about what was observed or whether a situation is in violation of the protocol. Subsequently, these reports also become a valuable learning tool for employees in the field.

Once uploaded, the data is stored in a database for later reference. Assessments continue to be added as audits are performed to amass a large bank of data. In electronic format, that data (unlike handwritten notes) can be easily arranged for analysis. Reports can be generated using a large menu of criteria, including running statistics on a site over a period time or identifying instances of a certain violation. Mining your data in different ways helps identify root causes and end harmful trends so that real improvement can occur.

Comments: No Comments

Facing Food Recalls Pt 3: Coverage

This is the third in a series of articles on food product recalls.

One form of protection from the economic and reputational damages of a food recall event can be to transfer risk through an insurance policy that is specifically designed to respond to a recall event.

Are You Covered?

Business Owner’s Insurance Policy “BOP” provides most enterprises with two main forms of coverage: Commercial General Liability (CGL) and Business Property. Many food and beverage companies believe that basic CGL insurance coverage will provide protection in the event of a product recall. In reality, CGL policies typically contain an exclusion (Recall of Products, Work or Impaired Property) that precludes coverage for any claims associated with a product recall or withdrawal.

Because most CGL policies do not cover recall-related losses, separate Product Recall, Business Interruption, or similar types of insurance can provide protection to reduce the potential financial impacts of a recall event. Companies can purchase either first-party or third-party Product Recall policies, or both.

First-party policies provide coverage for the company’s own economic loss incurred due to a recall. These losses may include:

- Business interruption

- Lost profit

- Recall expenses

- Expenses to respond to adverse publicity and rebuild a brand’s image

- Consultant and adviser costs

Third-party coverage applies to economic loss incurred by third parties (e.g., distributors, wholesalers, customers) who may be impacted by a recall event. This could include broad coverage for numerous costs associated with the following:

- Removal of recalled product from stores

- Transportation and disposal of the product

- Notification to third parties of the recall

- Additional personnel/overtime

- Cleaning equipment

- Laboratory analysis

Business Interruption insurance is another coverage that may cover not only catastrophic losses, but also food recall events. If purchased, it is important to make sure that the Business Interruption coverage works hand-in-hand with Product Recall coverage.

What to Look for in a Policy

Product Recall insurance should be specifically tailored to meet the needs of the company. Here are some things that a company should ask when exploring Product Recall/Contamination insurance:

- Will the policy cover recalls where there is limited likelihood of bodily injury (e.g., class II or class III recall that is less severe)? What if a recall is requested (vs. ordered) by the FDA or USDA?

- Will the policy cover loss from an FDA administrative detention?

- What happens if the company experiences financial loss due to a recall and then the facts underlying the recall turn out to be incorrect? Are those losses still covered?

- Does the policy exclude coverage if the recall was due to a problem with a competitor’s product? What if the product breaches a warranty of fitness?

- Does the policy provide coverage for claims by third parties (e.g., customers)?

- Does the policy cover lost profits/revenue? What about logistics and repair costs (e.g., shipping and destruction, public relations, product replacement, and reputation/brand damage)? How is the loss calculated?

*****

Read:

Comments: No Comments

RMP Reconsideration Proposed Rule

Chemicals are an important part of many aspects of our lives; however, improper handling and management of chemicals can result in catastrophic releases that have severe and lasting impacts—loss of life, injury, property damage, community disruption.

The USEPA’s Risk Management Plan (RMP) Rule (Section 112(r) of the Clean Air Act Amendments) is aimed at reducing the frequency and severity of accidental chemical releases. While the intent of the RMP Rule is positive, there has been much controversy over what the rule requires. This has resulted most recently in the RMP Reconsideration Proposed Rule, which was published on May 30, 2018.

The History of Modernizing RMP

RMP regulations were first created in 1996 to protect first responders and communities adjacent to facilities with chemical substances. Changes to the original RMP Rule have been in progress since former President Obama issued Executive Order (EO) 1365, Improving Chemical Safety and Security, in August 2013. Modernizing policies and regulations—including the RMP Rule—falls under this umbrella.

A July 2014 Request for Information (RFI) sought initial comment on potential revisions to RMP under the EO. This was followed by a Small Business Advocacy Review (SBAR) Panel discussion in November 2015. On March 14, 2016, the USEPA published Proposed Rule: Accidental Release Prevention Requirements: Risk Management Programs Under the Clean Air Act, Section 112(r)(7), outlining proposed amendments to the RMP Rule.

The much anticipated final RMP Amendments were published in the Federal Register on January 13, 2017. According to the USEPA, these amendments were intended to:

- Prevent catastrophic accidents by improving accident prevention program requirements

- Enhance emergency preparedness to ensure coordination between facilities and local communities

- Improve information access to help the public understand the risks at RMP facilities

- Improve third-party audits at RMP facilities

After the USEPA published the final rule, many industry groups and several states filed challenges and petitions, arguing that the rule was overly burdensome, created potential security risks, and did not properly coordinate with OSHA’s Process Safety Management (PSM) standard. Under the Trump administration, the USEPA delayed the effective date of the rule until February 2019 and announced its plan to reconsider the rule’s provisions.

Reconsideration

That brings us full circle to the RMP Reconsideration Proposed Rule that was published at the end of May. According to the USEPA, this reconsideration proposes to:

- Maintain consistency of RMP accident prevention requirements with the OSHA PSM standard.

- Address security concerns.

- Reduce unnecessary regulations and regulatory costs.

- Revise compliance dates to provide necessary time for program changes

What’s Going?

USEPA Administrator Scott Pruitt said in a press release, “The rule proposes to reduce unnecessary regulatory burdens, address the concerns of stakeholders and emergency responders on the ground, and save Americans roughly $88 million a year.”

To accomplish this, the reconsideration proposes making the following changes:

- All accident prevention program provisions have been rescinded in the reconsideration so the USEPA can coordinate revisions with OSHA and keep regulatory costs in check. This includes repealing the requirements for conducting:

- Third-party audits

- Safer Technology and Alternatives Analysis (STAAs) as part of the process hazard analyses

- Root cause analyses as part of an accident investigation of a catastrophic release or near-miss

- Most of the public information availability provisions have been rescinded due to their redundancy and security concerns, particularly regarding specific chemical hazard information. The USEPA is proposing to retain the requirement for facilities to hold a public meeting within 90 days of a reportable incident.

What’s Staying?

Many of the emergency coordination and exercise provisions of the Amendments rule are staying–but are being modified to address security concerns and provide more flexibility. The Reconsideration Proposed Rule still requires facilities to:

- Coordinate response needs at least annual with local emergency planning councils (LEPCs) and response organizations, and to document these activities

- Provide emergency action plans, response plans, updated emergency contact information, and other information necessary for developing and implementing the local emergency response plan to LEPCs

- Perform annual exercises to test emergency response notification mechanisms (Program 2 and 3 facilities)

Looking Ahead

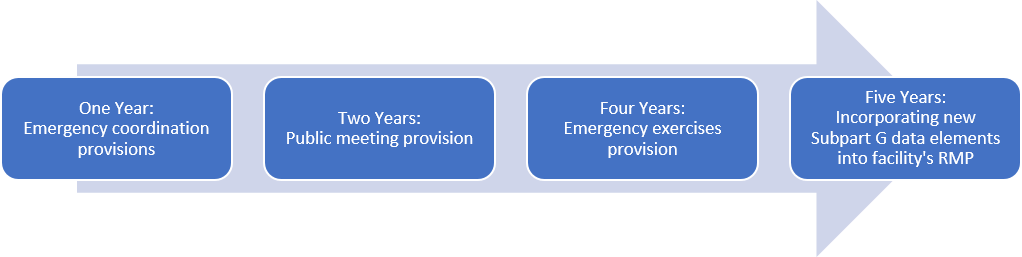

The proposed rule is available for public comment for 60 days after its publication date (May 30, 2018). In addition, a public hearing is scheduled for June 14, 2018. If the Reconsideration Proposed Rule is published, compliance dates will be as follows based on the effective date of the final rule.

For more information, visit the USEPA website on the RMP Reconsideration Proposed Rule.