Comments: No Comments

Food Chemical Safety

Safety Focus

Food chemical safety is an area that is becoming a growing public concern, especially with states including California, Illinois, and New York challenging the safety of certain food additives and other chemicals used in food. Is food safe to eat if it has chemicals?

Chemical Presence in Food

The truth is…all our food is made up of chemicals. Some naturally exist in whole foods and provide nutrition. For example, the potassium in bananas is a chemical. Some chemicals, like environmental contaminants, get into food when crops absorb them from soil, water, or air. Process contaminants (e.g., undesired chemical byproducts) can also form during food processing, particularly when heating, drying, or fermenting foods.

Chemicals may also be added to food for a variety of reasons:

- Create additional nutritional benefits (e.g., vitamins A and D being added to milk).

- Provide protection from pathogens that could make people sick.

- Enhance food by adding flavor, improving texture, and changing appearance.

- Preserve quality by preventing spoilage or extending shelf life.

FDA Authorization

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) must authorize any chemical added to food for use as a food or color additive before it may be used, unless the substance is generally recognized as safe (GRAS). Through its pre-market review programs, FDA reviews all relevant information about the chemical before providing its authorization, including information about:

- The identity of the chemical, including its chemical structure and data on other similar substances.

- How the substance will be used, its level of use, and the amount people may be exposed to in food.

- Toxicology, safety data, and other information to show the substance is safe at calculated exposure levels.

How Much Is Too Much?

The presence of a chemical does not determine whether a food is safe to eat. Rather, it is the amount that counts.

FDA scientifically assesses the safe amount of a chemical in food by comparing how much chemical is in the food and how much someone is likely to consume daily with other safety data to determine whether a food is safe to eat. Any chemical has the potential to be harmful at a certain level, which is why this multi-pronged evaluation and extensive calculations are important.

FDA determines an Acceptable Daily Intake level for the chemical. This level has a “built-in” safety margin to ensure the allowable daily amount is actually much lower than the level known to have a possible adverse health effect.

When Food Chemicals Become Unsafe

Authorized chemicals normally used in foods as additives and preservatives can become hazardous when they are unintentionally added or are present beyond the established limits. When this happens, it can cause immediate illness and/or long-term health effects on consumers. FDA monitors the food supply for chemical contaminants and takes action when the level of a contaminant causes a food to be unsafe. Situations such as this result in food safety alerts, recalls, and withdrawals from the market.

FDA helps safeguard the food supply by evaluating the use of chemicals as food ingredients and substances that come into contact with food (e.g., packaging, storing, handling). But ultimately, food manufacturers are responsible for marketing safe foods and ensuring that they meet FDA requirements. The manufacturers are required to implement preventive controls to significantly minimize or prevent exposure to chemicals in foods that may be hazardous to human health.

More information can be found on food chemical safety at the following websites:

World Brewing Congress 2024: Don’t Miss KTL on the Food Safety Panel

KTL is excited to be participating in the 2024 World Brewing Congress (WBC) in Minneapolis, MN, August 17-20, 2024. WBC 2024 aims to provide a compass for the brewing community to chart its course through the challenges that brewers and brewing professionals encounter on a global scale.

KTL will be a panelist for the following session:

Food Safety: Requirements, Programs, Experiences & Culture in Brewing

August 20, 2024 | 10:00-11:15 am | KTL Panelist: Estefania Lopez

Beer is food. This session will introduce you to basic food safety programs and regulatory requirements needed in order to produce a safe and quality product that your customers will keep coming back to and enjoy time after time.

Comments: No Comments

Produce Traceability: Uncovering the Gaps in Your Program

The produce industry handles an estimated six billion cases of produce in the U.S. each year. Because a significant portion of this produce travels through the supply chain to reach customers, many produce companies already have some level of traceability program in place. With the finalization of the Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) Food Traceability Rule, the question is whether these existing traceability programs, systems, and procedures meet regulatory requirements.

KTL’s recent article in Food Safety Tech walks you through how to conduct a gap assessment to determine what requirements your existing programs already meet and identify where improvements are needed to comply with the final Food Traceability Rule by the January 2026 deadline.

Comments: No Comments

Produce Traceability: 4 Steps to Get Started

On November 21, 2022, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) published the Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA) Final Rule: Requirements for Additional Traceability Records for Certain Foods (Food Traceability Rule). With the effective date for updated recordkeeping approaching in January 2026, traceability is a top priority for most organizations working in the food industry. Produce companies are especially impacted by traceability requirements as the first step in the food supply chain.

KTL’s recent article in Food Safety Tech outlines four steps to help any produce company prepare to meet FDA’s traceability requirements.

Comments: No Comments

Insights from the 2024 Food Safety Summit

The Food Safety Summit brings together the food safety community to learn more about today’s most crucial elements of food safety—from regulatory concerns and current industry trends to ongoing challenges and the latest technology and solutions.

This year’s Summit, held earlier in May, proved once again to be an engaging and informative meeting for those in attendance. Throughout the Summit, KTL’s food safety experts observed several common themes and challenges that the food industry is facing — challenges that your business may be encountering today. We sat down with KTL’s attendees—Roberto Bellavia, April Greene, Estefania Lopez, and Joe Tell—to get their key insights from the Summit.

What technical topics were covered at the Summit? What seemed to gain the most interest from participants (i.e., “hot topics”)?

The Summit covered a range of content, including food safety culture, artificial intelligence (AI), HACCP, collaborating with regulators, microbial process control and sanitary design, sustainability, root cause analysis, e-commerce, state laws and regulations, viruses and pathogens in foods, food code adoption/harmonization, software, produce safety, and women in food safety. Of these, there were two particularly hot topics we heard about time and again this year: food traceability and cannabis.

Food Traceability. The implementation date for the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA) Final Rule: Requirements for Additional Traceability Records for Certain Foods (Food Traceability Rule) is January 2026. Impending deadlines have a lot of people talking, as many companies are starting to realize that having multiple software solutions to handle their food safety information is going to make complying with the new traceability requirements a nightmare. Having a robust document/records management system is essential for maintaining the vast number of documents required by regulations and standards, particularly the Food Traceability Rule.

Cannabis. There have been multiple instances of cannabis-infused products with unlisted ingredients falling through the cracks of regulations, creating potential negative impacts on human health and significant reputational issues. This, coupled with the recent information asserting the Drug Enforcement Agency’s (DEA) plans to reschedule marijuana from Schedule I to Schedule III under the Controlled Substances Act (CSA), is pushing many states to protect consumers of food and beverages infused with cannabis in the absence of federal guidance. State regulatory agencies are essentially playing a game of “whack-a-mole” with cannabis companies as they try to navigate where cannabis products fall: Food? Drug? Dietary Supplement? One regulator at the Summit stated that cannabis regulation is a modern day wild, wild west.

Are there any *new* food safety trends you heard about that companies should have on their radar?

There were several talks focused on sustainability at the Summit this year. The FDA, U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), and Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) released a joint strategy for reducing food loss and waste for organics in December 2023. They are working to create multiple pathways to make it easier for restaurants, farms, and manufacturers to divert good, nutritious food from landfills to food banks. The strategy also focuses on educating consumers, so they understand how to handle food waste in their own homes.

In addition, there were multiple conversations regarding the significant impacts of global climate change on the food supply chain. ISO’s recent Climate Change Amendments, as well as the Securities Exchange Commission (SEC) Climate-Related Disclosure Rule (which was recently stayed on March 15, 2024) continue to emphasize the importance of accounting for and managing climate change impacts. Companies are at a pivotal point where they need to make decisions regarding their sustainability efforts and how they proceed to meet regulatory and supply chain drivers.

You talked to a lot of different people and companies. What are some of the biggest challenges they are currently facing?

There is a lot of frustration amongst companies, federal regulatory authorities (e.g., FDA, USDA), and state regulatory bodies regarding regulations and guidance for emerging issues like new contaminants (e.g., pathogens, viruses, etc.) and security concerns not being addressed quickly enough. One example brought up during the Town Hall: Real-Time Conversation with FDA, CDC, USDA, and AFDO was the new strain of avian flu being found in raw milk. Because it takes time for testing to be completed—and then subsequent guidance to be created—companies are left wondering what to do about this risk. Most companies cannot very well just stop production during this window of uncertainty without significant impacts. During the presentation, regulators said they are trying to figure out ways to keep up with the speed of change and the associated risks that are constantly present in the food industry.

Lack of support and resources for those managing food safety programs remains an ongoing challenge for many organizations. It is not uncommon for a company’s food safety and quality assurance (FSQA) team/department to comprise only one individual. And while companies seem willing to provide information technology (IT) tools to help manage food safety requirements, many attendees expressed frustration with the lack of harmonization between the various IT solutions, making them ineffective and inefficient to use. See more below.

KTL presented on using existing Microsoft solutions to develop a food safety management system (FSMS). What role do you see IT solutions playing in the food industry?

As stated above, we talked with many companies that have purchased various software solutions with the expectation they would work together; in reality, many of these tools operate independently. As a result, companies are getting frustrated because they have invested time, money, and effort in these tools but have not realized business efficiencies.

There are significant benefits to implementing IT tools that “talk” to each other versus these siloed systems. As our presentation demonstrated, KTL focuses on leveraging Microsoft 365—which most companies are already using—to create integrated systems with various apps/tools that address specific FSQA and operational needs. This approach allows companies to manage various compliance and certification requirements, enables staff to carry out daily tasks and manage operations, and supports operational decision making by tracking and trending data more effectively and efficiently.

Given what you heard, what should companies in the food industry be doing now to plan for the future?

We walked away from the Summit with some key takeaways in some key areas:

Traceability. Companies throughout the supply chain will be impacted by the Food Traceability Rule—potentially even if they don’t have products on the Food Traceability List (FTL). Take time to understand the Rule requirements and how they apply to your operations and to train employees at all levels so they understand their responsibilities. This is an excellent time to perform traceability exercises for everything to help identify gaps, test protocols and verify effectiveness, implement corrective actions, and ensure adequate traceability processes are in place before the January 2026 deadline. It will be especially important to begin or renew communication with contacts throughout the supply chain to facilitate documentation, information sharing, and collaboration. Investing in a good IT solution that integrates with your FSMS will help to further streamline the process.

Cannabis. Companies getting involved in the growing cannabis industry need to stay on top of the rapidly changing regulatory environment. Assess operations, determine what standards might be appropriate, identify gaps in existing programs, prepare for a new regulatory framework—state and/or federal—and begin implementing solutions to eliminate risks.

Food loss and waste. We have all heard reduce, reuse, recycle from the EPA. Now the USDA, FDA, and various food safety certification schemes are holding companies in the food industry accountable for reducing food waste and preventing food loss. Before this becomes mandatory, companies should begin the process of identifying targets and associated methods for reducing food loss and waste.

Food safety outbreaks and recalls. Food safety professionals should be continually monitoring information regarding foodborne illness outbreaks. Companies can reduce their risks by staying informed about emerging food safety threats, identifying and assessing vulnerabilities in their facilities, implementing protocols to help mitigate impacts to consumers, challenging food defense programs by conducting intrusion tests, and developing a comprehensive Crisis Management Plan to manage human health and reputational impacts.

Produce safety. In July 2022, FDA extended the compliance dates for the pre-harvest agricultural water requirements for non-sprout covered produce. Covered farms are subject to the requirements of 21 CFR Part 112 Subpart E if they use water during the growing, harvesting, packing, or holding of covered produce in a way that meets the definition of “agricultural water.” If you fall under this category, note the new compliance dates, which differ depending on farm size:

- January 26, 2025: Very small businesses.

- January 26, 2024: Small businesses.

- January 26, 2023: All other businesses.

Companies receiving produce need to establish the criteria for information that will be requested from the farm upon delivery of produce, such as Certificate of Analysis (CoA). If conducting supplier audits for farms, include the requirements of the Rule into audit criteria.

With all these challenges and trends simultaneously competing for attention—and with fewer resources to manage it all—companies need to assess priorities, needs, and requirements and create a plan for how to meet them.

Comments: No Comments

Plastics Recycling for Food-Contact Materials

According to the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), we produce about 400 million tons of plastic waste every year globally. Approximately 36% of that plastic is used in packaging, including single-use plastic products for food and beverage containers.

The European Commission estimates that approximately 50% of plastic packaging in the European Union (EU) is used for the food and beverage industry. In the U.S., food packaging comprises approximately two-thirds of all packaging material produced, and correspondingly, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) cites that food and food packaging materials make up almost half of all municipal solid waste.

Food packaging is used to help make food clean, safe, transportable, and shelf stable. Unfortunately, most of it is single use and is not recycled or reused. But there is a growing trend throughout the U.S., as well as in Canada and the EU, to increase the use of post-consumer recycled (PCR) materials in packaging products, including plastic.

Regulatory Background

California enacted the first minimum recycled content laws in the U.S. in 1990 for fiberglass, glass containers, plastic containers, and plastic trash bags. Fast forward to late 2023, and the Association of Plastics Recyclers (APR) indicates that seven states are currently in various stages of developing and/or implementing state minimum recycled content laws, including California, Maine, Washington, New Jersey, Connecticut, Maryland, and New York.

In general, these laws establish incremental minimum recycled content requirements for various packaging materials and associated timelines for compliance. Impacted products include plastic beverage bottles, plastic carryout bags, trash bags, household cleaning and personal care products, and others. Some laws allow for averaging recycled content across a company’s covered products portfolio to meet requirements. Some states require third-party certification to ensure accountability.

The New Jersey Recycled Content Law, which recently came into effect on January 18, 2024, is considered one of the most ambitious recycled content laws to date, as it goes beyond traditional rules to cover rigid plastic containers.

Given current and potential upcoming legislation, manufacturers and retailers alike must be aware of which products are covered by recycled content standards, as there may be restrictions on the use and sale of products that do not comply.

Plastic Recycling for Food-Contact Materials

According to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), there are only a few major varieties of plastic that meet the Agency’s guidelines for safe contact with food and that can be considered food grade and FDA-compliant. To be FDA-compliant, packaging must be able to withstand whatever environment it will be used in (e.g., extremely hot oven for cooking, freezing temperatures, and cleaning and sanitization). The packaging material must also be compatible with the type of food it will be in contact with and must not leach any chemicals if the food is acidic or has high moisture content.

The following plastics are generally considered safe for food:

- High-density polyethylene (HDPE), the most common household plastic, is used to make beverage bottles, butter containers, cereal box liners, and thicker food storage buckets. FDA evaluates the use of recycled HDPE on a case-by-case basis, as it can become unsafe in the recycling process.

- Low-density polyethylene (LDPE) is similar to HDPE but less rigid. It is used for products like squeeze bottles, plastic wrap, six-pack rings, etc. While LDPE is chemical-resistant and does not leach, recycled LDPE is not deemed safe for food contact.

- Polycarbonate resin (PCR) has presented some concerns about the presence of bisphenol A (BPA); however, FDA studies conclude that intake from BPA in plastic is very low and does not have apparent negative health impacts.

- Polypropylene (PP) is most often used for single-serve containers (e.g., yogurt, cottage cheese) and reusable food storage containers. It is microwave safe and nonvolatile.

- Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) is used to make any plastic jars and beverage containers (e.g., 2-liter bottles, peanut butter jars, salad dressing containers, etc.). It repels microorganisms and does not corrode.

While many of these plastics are only FDA-compliant and food safe in their unrecycled state, recycled PET is an FDA-approved plastic for food contact. Most plastic food packaging that is not made of PET cannot be recycled into new food packaging due to missing processes (i.e., waste collection, separation, decontamination) and other safety concerns. These other types of plastic food packaging are typically only downcycled or not recycled at all.

Recycling Responsibilities

Manufacturers of food-contact packaging made from recycled plastic are responsible for ensuring that recycled material meets the same specifications for virgin material, as outlined in 21 CFR parts 174-179. The regulations state that any substance used as a component of articles that contact food shall be of a purity suitable for its intended use.

Because recycled food-contact materials have content that is recovered from waste, it may be contaminated with substances originating from previous use or other waste—and that contamination may end up in our food and be harmful to human health. The FDA cites the following main safety concerns with the use of PCR plastic materials in food contact articles:

- Contaminants from the PCR material may appear in the final food-contact product made from the recycled material.

- PCR material that may not be regulated for food-contact use may be incorporated into food-contact material.

- Adjuvants in the PCR plastic may not comply with the regulations for food contact use.

Although not required by law, recyclers of plastic intended for food-contact use may submit information on their recycling process to FDA for evaluation. In turn, FDA will consider each proposed use of recycled plastic on a case-by-case basis and issue informal advice as to whether the recycling process is expected to produce food grade, FDA-compliant PCR plastic based on the following:

- Complete description of the recycling process, including a description of the source of the PCR plastic, any source controls in place, and a description of steps taken to ensure the recyclable plastic is not contaminated at any point.

- Results of any tests performed to show that the recycling process removes possible incidental contaminants.

- Description of the proposed conditions of use of the plastic (e.g., temperature, type of food, duration of contact, repeated or single use).

Recycling plastic food packaging is widely seen as an opportunity to reduce our environmental impacts across the globe. While plastic food packaging recycling is limited extent due to material properties, waste management processes, and chemical safety concerns, legislation is pushing recycling forward where it is safe. Given this, manufacturers and retailers must be aware of which products are covered by recycled content standards and make plans to meet established timelines for minimum recycled content requirements to avoid restrictions on the use and sale of products that do not comply.

KTL to Present at MBAA District Carolinas Technical Conference

KTL will be joining industry experts at the 2024 Master Brewers Association of America’s (MBAA) District Carolina Technical Conference to discuss food safety and regulatory implications of producing nonalcoholic and low-alcohol beer (NALAB).

MBAA District Carolinas 2024 Spring Technical Conference

May 4, 2024

Hopfly Brewing Company | Charlotte, NC

KTL Presentation: Food Safety and Regulatory Implications of Producing Nonalcoholic and Low-Alcohol Beer (NALAB)

The demand for NALAB has increased significantly in the past few years and is projected to continue. KTL’s presentation will describe the complexities associated with adding a NALAB beverage to a product portfolio and break down the requirements and considerations into actionable pieces. It will also discuss relevant food safety risks in traditional beer, such as allergen cross-contamination, chemical inclusion, and foreign object inclusion. Specifically, the presentation will cover the following:

- Interpretation and breakdown of the regulatory requirements for NALAB products.

- Differences in FDA regulatory requirements for traditional beer versus NALAB products.

- Known or reasonably foreseeable food safety hazards associated with traditional beer and NALAB products.

- Strategies that brewers can take to minimize food safety hazards.

Don’t Miss KTL at the 2024 Food Safety Summit

As one of the premier events in the food industry, the Food Safety Summit provides a comprehensive conference and expo for attendees to learn from subject matter experts, exchange ideas, and find solutions to current industry challenges.

- When: May 6-9, 2024

- Where: Donald Stephens Convention Center, Rosemont, Illinois

- Who: Retailers, food processors, distributors, food manufacturers, growers, foodservice, testing laboratories, importing/exporting, law firms, and other food safety professionals

- Find KTL: Stop by our booth (#406) in the exhibit hall!

Tech Tent Case Study Presentation

Be sure to also update your agenda to attend KTL’s Tech Tent presentation on Thursday, May 9 at 11:15 am CT:

Case Study: Leveraging Existing Microsoft® Software to Develop a Robust FSMS

KTL will present a case study demonstrating how Italian Frozen Foods (IFF) USA is leveraging the company’s existing software—Microsoft Power Platform with SharePoint®—to elevate its food safety management system (FSMS) and effectively manage food safety compliance documentation, data, and certification requirements.

- Learn how you can use the software you already have to develop a robust FSMS.

- Understand the approach and process required to ensure successful development and implementation.

- Observe in practice how an integrated system can help organize, control, analyze, and visualize information so you remain in compliance and operate more efficiently.

FAQs on ISO’s New Climate Change Amendments

Effective February 23, 2024, the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) is integrating climate change considerations into all management system standards through its Climate Change Amendments. These Amendments ensure climate change impacts are considered by all organizations in their management system design and implementation.

ISO’s recent action supports the London Declaration on Climate Change of September 2021, which establishes ISO’s commitment to combatting climate change through its standards and publications. The aim of the recent Amendments is to make climate change an integral part of management systems design and implementation to help guide organizational strategy and policy.

What are the changes?

The Climate Change Amendments explicitly require climate change considerations in all existing and future ISO management systems standards, as incorporated into the Harmonized Structure (Appendix 2 of the Annex SL in the ISO/IEC Directives Part 1 Consolidated ISO Supplement). More specifically, the Amendments add the following two new statements to Annex SL for organizations to consider the effects of climate change on the management system’s ability to achieve its intended results:

- Clause 4.1: The organization shall determine whether climate change is a relevant issue, as it relates to understanding the organization and its context.

- Clause 4.2: NOTE: Relevant interested parties can have requirements related to climate change, pertaining to understanding the needs and expectations of interested parties.

The broad scope of these Amendments (i.e., impacting all standards) reflects ISO’s commitment to integrating climate considerations across diverse operational areas (e.g., environment, quality, safety, food safety, security, business continuity, etc.).

What do these changes require?

The original intent and requirements of Clauses 4.1 and 4.2 remain unchanged; however, the Amendments now require organizations to consider the relevance of climate change risks and impacts on the management system(s).

Potential climate change issues will likely differ for the various standards. The Amendments ensure these various risks are considered for each standard and, if actions are required, allow the organization to effectively plan for them in the management system.

What do certified organizations need to do?

Organizations that are certified—or are planning for certification—need to make sure they consider climate change aspects and risks in the development, maintenance, and effectiveness of their management system(s).

The Amendments specifically require these organizations to evaluate and determine whether climate change is a relevant issue within their management system(s). If the answer is yes, the organization then must consider climate change in a risk evaluation within the scope of their management systems. Where relevant, organizations are further encouraged to integrate climate change into their strategic objectives and risk mitigation efforts. The Amendments do not require organizations to do anything about climate change beyond considering the impacts on the management system’s ability to achieve its intended results.

What is the timeline?

The Amendments are effective as of the date of publication. There is no transition for implementation.

Certification bodies and auditors will cover the Amendments in audit activities when assessing this section of a management system. The audit will ensure climate change is considered and, if determined to be a relevant issue, included in company objectives and risk mitigation efforts. If climate change is deemed not relevant, the audit will assess the organization’s process for making this determination.

Will new certifications be issued?

Because the changes are considered a clarification, ISO issued them in the form of an amendment. New standards will not be republished until new versions are released; therefore, the publication year of each ISO standard will not change, and no new certifications will be issued.

What are the benefits of these changes?

The Climate Change Amendments underscore the importance of understanding and addressing the impacts of climate change. By publishing the Amendments in Annex SL, ISO is leveraging the widespread adoption of all ISO management system standards across operational areas to integrate environmental stewardship into organizational practices, promote sustainability, and drive climate change action on a global scale.

For certified organizations, the Amendments are intended to enhance organizational resilience and adaptability to climate-related risks. Considering climate change in this way can significantly contribute to business sustainability and long-term success by:

- Ensuring regulatory compliance (e.g., emission limits, sustainability reporting, etc.).

- Creating positive brand reputation as a sustainable company and associated customer loyalty.

- Managing risks and opportunities associated with supply chain disruptions, energy efficiency initiatives, employee health and safety, natural disasters, etc.

- Engaging employees and attracting new talent who prioritizes sustainability.

- Providing access to markets and investors that have sustainability requirements.

Comments: No Comments

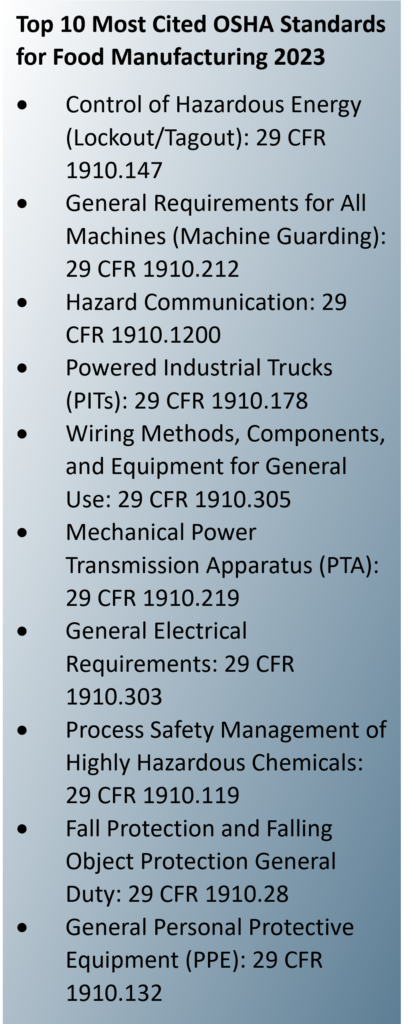

Focus on Employee Safety in the Food Industry

Safety hazards exist in every manufacturing environment. The food industry is no exception. Between October 2018 and September 2019, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) issued a total of 1,168 citations resulting in over $7 million in fines to the food manufacturing industry alone.

Occupational safety and health risks in food manufacturing are often heightened because of the nature of the product (i.e., food or drink) being manufactured. Even food safety measures taken to prevent contamination and ensure food safety can carry inherent occupational safety and health risks.

While food safety is paramount for any company operating in the food industry, a company cannot stay in business if they do not take the appropriate measures to keep employees healthy and safe.

Common Safety Hazards in the Food Industry

Lockout/tagout and machine guarding recurringly top OSHA’s annual list of the most frequently cited standards in food manufacturing. In fact, the most expensive OSHA fines of 2023 involved two food manufacturers and violations concerning machine guarding and lockout/tagout.

Lockout/Tagout

Employees need to be protected against the unexpected startup or release of energy. Lockout/tagout involves properly de-energizing and securing equipment so it cannot be operated unsafely when a machine needs service or repair. When employees work in a fast-paced environment, they may not take the required steps to first properly de-energize the equipment. As a result, approximately 1,000 workers die each year due to unexpected operation of equipment and/or release of stored energy. Machines and electrical equipment must be properly shut down, de-energized, and locked when servicing.

Machine Guarding

Moving machine parts have the potential to cause severe workplace injuries, such as crushed fingers or hands, amputations, burns, blindness—and most food processing machinery includes pinch points (i.e., blades, rolling parts, presses, etc.) that can put workers at increased risk. Safeguards for machine parts, functions, and processes are essential for controlling hazards and protecting workers from these otherwise preventable injuries.

Other Common Safety Hazards

- Ergonomics. Many food manufacturing jobs involve repetitive motion that can cause musculoskeletal disorders.

- Slips, trips, and falls. Sticky or wet products and frequent cleaning can both contribute to slippery work surfaces that increase the risk for slips, trips, and falls. The high volume of liquids used in food manufacturing and processing creates regular employee exposure to wet surfaces.

- Chemicals and harmful substances. Food facilities rely on various chemical sanitizers and disinfectants to prevent contamination. In addition, anhydrous ammonia, a common refrigerant used in food facilities, is very hazardous (i.e., corrosive, flammable, and explosive), even in small spaces.

- Cut hazards. Knives and other blades are common equipment in food processing plants. Dull blades cause more accidents because they are harder to work with, require more pressure, and may slip more easily. Blades should be sharpened, and employees should wear appropriate PPE.

OSHA Response: Local Emphasis Programs

Between 2016 and 2020, OSHA investigated fatalities, amputations, fractures, and crushed hands and fingers at food manufacturing facilities and identified the primary causes as failure to control hazardous energy or implement adequate machine guarding. In Wisconsin, Bureau of Labor and Statistics (BLS) data from 2011-2020 show that food manufacturing injury rates were consistently higher than the averages for all Wisconsin manufacturing companies. In 2019, OSHA found that food production workers in Ohio had a nearly 57% higher rate of amputations and 16% higher rate of fractures; in Illinois, these rates were 29% higher for amputations and 14% higher for fractures compared to private sector manufacturing.

In 2022, OSHA Region 5 established two Local Emphasis Programs (LEPs)—one for Wisconsin and one for Illinois and Ohio— to encourage employers to identify, reduce, and eliminate exposure to machine hazards during production activities and off-shift sanitation, service, and maintenance tasks (i.e., machine guarding and hazardous energy control – lockout/tagout). These LEPs run through at least 2027 and focus on reducing fatalities and injuries through outreach, education, training, and enforcement activities.

The LEP empowers OSHA to schedule and inspect food industry employers whose injury rates exceed the state average among all manufacturers. The scope of inspections conducted under the LEP focus on reviewing:

- Production operations, sanitation processes, and working conditions.

- Injury and illness records (i.e., OSHA 300 logs), particularly injuries pointing to deficiencies in machine guarding or the hazardous energy control program.

- Machine guarding hazards associated with points of operation, ingoing nip points, and moving or rotating parts of food processing equipment.

- Deficiencies in the hazardous energy control program associated with equipment service, maintenance, setup, and sanitation.

- Hazards associated with chemical burns from corrosives, such as those used for cleaning and sanitizing.

Prepare Your Facility…Protect Your Workers

If you fall under an OSHA LEP, you need to prepare your facility. Even if you don’t, you need to protect your workers.

- Prepare and maintain your OSHA 300 log with any work-related injuries and illnesses. KTL’s OSHA 300 PowerApp can make it easier to collect, search, analyze, store, and aggregate data so it is available when needed.

- Conduct a thorough hazard analysis of the facility, operations, and processes to identify potential safety hazards. The hazard analysis should answer what could potentially go wrong, what the associated consequences are, and how they can be prevented or eliminated.

- Develop, implement, and maintain the appropriate safety programs, procedures, and instructions. A safety management system that aligns with current food safety systems can provide resources to help companies identify and manage safety risks and an organizing framework for policies, procedures, and practices, including:

- Engineering controls for dangerous equipment, including machine guarding.

- Written energy control program and lockout/tagout procedures specific to each piece of equipment.

- Emergency response programs.

- Proper maintenance, cleaning, and sanitation procedures and schedules.

- Guidelines for proper use, care, and replacement of PPE.

- Train your staff. Workers need to have appropriate training, including use of PPE, hazards of extreme temperatures, material handling, hazard communication, lockout/tagout procedures, machine guarding procedures, etc. Initial safety training should be conducted when onboarding new employees, with refresher training provided annually to ensure competency. Training tracking systems allow for the centralized implementation, management, tracking, scheduling, assignment, and analysis of organizational training efforts.

- Provide proper PPE. Workers should be wearing proper footwear, gloves, safety glasses, ear plugs, aprons, etc. and be provided with anti-slip mats to ensure safety.

- Ensure safety data sheets (SDS) are current and available to help identify hazardous chemicals and protect employees from exposure. Train workers on the chemicals used in the workplace, including first aid, what to do in the event of a release, identifying characteristics, proper procedures for working around or with the chemical, and appropriate PPE.

- Use visual communication (e.g., labels, signage) to help protect workers from hot surfaces, exposed moving parts, pressurized systems, hazardous chemicals, slippery surfaces, and more.

Finally, prioritize safety. Small steps can go a long way in making sure employees leave work safely versus becoming an OSHA statistic.